UAA anthropology professor explores indigenous identity among Alaska Natives

by Ted Kincaid |

Germany. What are the first things you think of? Lederhosen, beer steins, quaint Bavarian

villages, or maybe sporty Volkswagen cars? What about France? The Eiffel Tower, crepes

and haute couture? Australia? Koalas, didgeridoos, the Great Barrier Reef? Okay, you

get the idea. Now what about Alaska Native cultures? A little harder to answer? UAA

Associate Professor of Anthropology and Liberal Studies Phyllis Fast is working to

explore what those visual and cultural identifiers are for Alaska's 11 Native cultures,

including Athabascan; Unangax and Alutiiq (Sugpiaq); Yup'ik and Cup'ik; Inupiaq and

St. Lawrence Island Yupik; and Eyak, Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian.

Germany. What are the first things you think of? Lederhosen, beer steins, quaint Bavarian

villages, or maybe sporty Volkswagen cars? What about France? The Eiffel Tower, crepes

and haute couture? Australia? Koalas, didgeridoos, the Great Barrier Reef? Okay, you

get the idea. Now what about Alaska Native cultures? A little harder to answer? UAA

Associate Professor of Anthropology and Liberal Studies Phyllis Fast is working to

explore what those visual and cultural identifiers are for Alaska's 11 Native cultures,

including Athabascan; Unangax and Alutiiq (Sugpiaq); Yup'ik and Cup'ik; Inupiaq and

St. Lawrence Island Yupik; and Eyak, Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian.

Phyllis explains that many things in our day-to-day lives are borrowed heavily from cultures of the past, like, for example, the oval shape of a rain jacket's hood. She references the burka, often associated with the Middle East, which stems from nomadic desert people that had geographic and climatic reasons for wearing them. Same with the Alaska Native parka, designed to protect from the Arctic's extreme elements.

"There have been so many years of colonialism that many aspects of Alaska Native cultures have been forgotten," Phyllis says. "Often, young people don't realize there's a connection between something they use in their every day lives to something of their culture's past. They should be made aware of those connections and be proud of them-they need something to hang onto."

You could say that Phyllis' research is personal. A Koyukon Athabascan born and raised in Anchorage, Phyllis-also an artist-finds it important to understand more about how her own art represents her Alaska Native heritage. She asks herself, "What is it about my painting that makes it an 'Athabascan' piece of art?"

She gives the example of her friend Donita Hensley's artwork that involves the weaving of plastic bags to create something that looks and feels like it was made of grass. In Donita's home village of Tyonek in the Iliamna region, women collect plastic sacks, cut them up into strips and crochet them together. "It's an old tradition-working with what's available to you, saving everything, recycling it and using it in a practical way," Phyllis says. "It's these simple things we do that stem from our old traditions, but they may be invisible to us because of the many changes that have happened over the years."

Phyllis's research goes beyond the traditional anthropological ways of looking at

clues from the past. She explains that anthropology in the early 20th century suggests

that something has to be a specific shape or color for it to be associated with a

certain time period or culture. "I'm trying to look a little deeper," she says. "What

I'm looking for is far more fundamental, more human."

Phyllis's research goes beyond the traditional anthropological ways of looking at

clues from the past. She explains that anthropology in the early 20th century suggests

that something has to be a specific shape or color for it to be associated with a

certain time period or culture. "I'm trying to look a little deeper," she says. "What

I'm looking for is far more fundamental, more human."

Over the years, Phyllis has been collecting images and speaking with many of her fellow Alaska Native artists to learn how they incorporate elements of their heritage into their works of art. "There are so many great artists living right here in Anchorage to draw inspiration from and to learn from," she says.

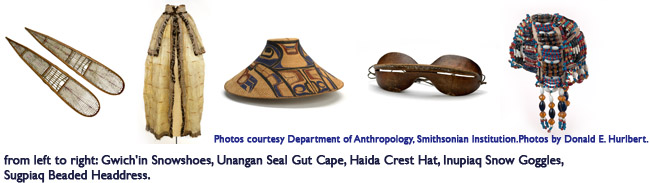

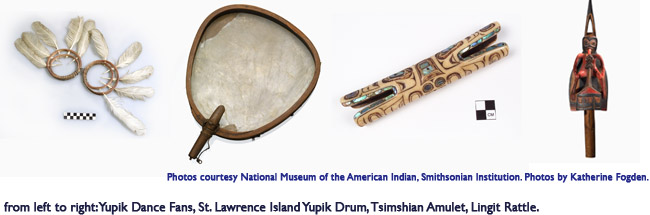

Phyllis explains that there are core visual symbols for each Alaska Native culture. She says that for Athabascans, a common shape is an elongated oval that can be seen in snowshoe, canoe and parka hood designs. For the Inupiaq and St. Lawrence Island Yupik cultures, a recognized shape is the circular "sunshine parka" featuring a full fur ruff. The Yup'ik and Cup'ik-very women-centric cultures-often use the nucleated circle in designs, in reference to the breast or womb. The Unangax and Alutiiq are largely associated with the conical shaped bentwood hat, and for the Eyak, Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian a typical shape is the ovoid, which is also prevalent in Northwest Coastal Indian communities in Washington and Oregon. "These shapes are deeply a part of our traditions," Phyllis says.

It's Phyllis's goal to highlight how these shapes from the past are brought forward into the future and to inspire today's young people with alternative ways to show pride in their Alaska Native heritage. "I feel that many young Natives hear, 'Oh, you don't speak the language so you're not really Alaska Native.' I want to make them aware of some of the nonverbal, artistic ways they can identify with their culture and express their heritage," she says.

Phyllis is on sabbatical for the 2012-13 academic year, but she's staying plenty busy writing and editing a textbook with her colleague Professor Kerry Feldman. The book, titled Alaska's First Peoples, is expected to publish next fall. Learn more about Phyllis and her work in her I AM UAA profile.

Check out a digital map of Alaska's indigenous peoples and languages created by the Alaska Native Language Center and UAA's Institute of Social and Economic Research. Learn more about Alaska Native cultures by visiting the Alaska Native Heritage Center website .

"UAA anthropology professor explores indigenous identity among Alaska Natives" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"UAA anthropology professor explores indigenous identity among Alaska Natives" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.