Breakthroughs at UAA in lung cell reactions to tobacco smoke exposure, sister-study examines smokeless Alaska Native iqmik

by Ted Kincaid |

We've all heard it before: Tobacco kills. According to the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention (CDC), cigarette smoke (first- and secondhand) is responsible for 1

in 5 deaths in the U.S. every year.

We've all heard it before: Tobacco kills. According to the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention (CDC), cigarette smoke (first- and secondhand) is responsible for 1

in 5 deaths in the U.S. every year.

Unfortunately for us, Alaska has a lot of adult smokers. The CDC reports that 21.5 percent of adult Alaskans light up (CDC's Tobacco Control State Highlights 2010). Given that the rates among all states range from 9.3 to 26.5 percent, Alaska actually falls in the "top 10."

So we know it's bad and Alaskans are at risk, but do we understand how smoke actually affects our lung tissue? And would quitting smoking now, after years of inhaling, really make a difference in lung health?

UAA Associate Professor of Medical Education and Biomedical Researcher Cindy Knall, Ph.D., has devoted her career to pinpointing how cells react to tobacco and the devastating consequences. She's recently made new discoveries and is applying her approach to iqmik, a widespread smokeless tobacco mixture popular among Alaska Natives.

Unzipping the detailsThe cells that make up the structure of your lungs provide a layer of protection from the exterior environment. Now, imagine a zipper between each cell that makes up that barrier. The teeth on those zippers are a group of proteins that form tight junctions. In a normal, healthy state, that zipper between cells is closed.

"My original research interest was in emphysema," explains Knall in her office at UAA's ConocoPhillips Integrated Science Building. "Not just immune system changes, but the changes in structures of the lung cells themselves as they're exposed to cigarette smoke."

Knall has found in past studies that cigarette smoke causes the zipper barrier between lung cells to open. But she wanted to know more. What mechanisms within cells were being triggered to cause the opening?

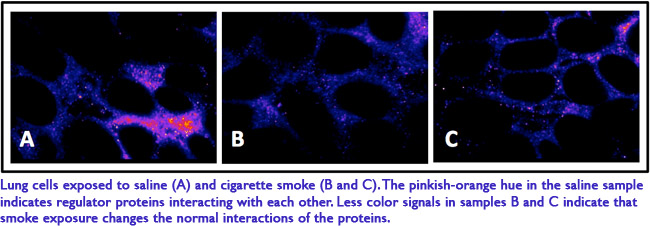

Recently, Knall and second-year UAA WWAMI medical student Stephanie Soiseth identified

two proteins within lung cells that physically change location when exposed to smoke.

Recently, Knall and second-year UAA WWAMI medical student Stephanie Soiseth identified

two proteins within lung cells that physically change location when exposed to smoke.

"These interior proteins are part of what help the cell maintain its shape and structure," Knall explains. "When the proteins change location as a reaction to cigarette smoke, it compromises that skeleton of proteins and may weaken the zipper closure with the neighboring cell."

With the zipper open, toxins, bacteria and viruses can enter the lung tissue unobstructed.

"It's been thought in the past that smoking causes wounds in the lung by killing the cells," she says. "What my lab has found is that there is, instead, a regulated response to the smoke. If we take the smoke away, the zipper closes again."

Point taken: Quitting smoking at any time is useful to reducing the harmful effects to lung health.

Next up: Does iqmik open a cell 'zipper,' too?

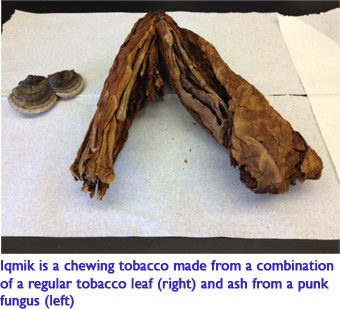

Similar to her smoke studies, Knall is now turning her attention to iqmik in order

to understand how nicotine from the tobacco leaf and punk fungus ash mixture enters

a user's system through oral cells. Does it open a cellular zipper, like cigarette

smoke does in the lungs? And is it more or less harmful than smoke or regular chewing

tobacco?

Similar to her smoke studies, Knall is now turning her attention to iqmik in order

to understand how nicotine from the tobacco leaf and punk fungus ash mixture enters

a user's system through oral cells. Does it open a cellular zipper, like cigarette

smoke does in the lungs? And is it more or less harmful than smoke or regular chewing

tobacco?

Knall's research over the past year has uncovered a few answers so far.

First, she and her team confirmed that iqmik does have a significantly higher pH than regular tobacco (10.6 versus 6.6) due to the addition of the punk fungus ash. It has been hypothesized that this high pH is a contributing factor in the absorption rate of iqmik into the cells of mouth tissue by changing the characteristics of the nicotine to a chemical form that is more easily absorbed. Knall is still developing detection methods for nicotine levels, but she says, "We think we'll see more nicotine in cells exposed to iqmik."

Second, she now has clear data showing that iqmik alters the expression of a universal gene that is a key marker of inflammation in humans. The gene itself, cyclooxygenase-2 (or COX-2), is also the target for certain arthritis medicines and is affected by regular chewing tobacco as well. "Iqmik had a more dramatic effect on the COX-2 gene than did the tobacco in our studies," says Knall, also indicating that they will be pursuing research on the inflammatory response of a larger panel of genes as their next step.

Knall is determined to help put an end to iqmik's underestimated effects through further

understanding the biological processes that iqmik triggers, and to discover if it

does so differently than regular chewing tobacco. Right now, it is estimated that

iqmik users in rural Alaska outnumber commercial tobacco users 2 to 1. There is also

a widespread opinion among users that iqmik is safer than commercial chewing tobacco

or cigarettes because of the lack of additives.

Knall is determined to help put an end to iqmik's underestimated effects through further

understanding the biological processes that iqmik triggers, and to discover if it

does so differently than regular chewing tobacco. Right now, it is estimated that

iqmik users in rural Alaska outnumber commercial tobacco users 2 to 1. There is also

a widespread opinion among users that iqmik is safer than commercial chewing tobacco

or cigarettes because of the lack of additives.

"As a researcher in Alaska, I feel a certain responsibility to the citizens of the state, and I'm being especially thoughtful about this project for cultural reasons," she says, explaining that, historically, preparers of iqmik would sometimes ask youth in the community to help pre-masticate the tobacco leaf and punk fungus mixture to form individual chews for their elders. Although that is no longer the practice since more education about the effects of nicotine have reached rural communities, Knall's hope is that further study of iqmik will highlight its risks as comparable to that of smoking.

Knall received funding for the iqmik studies through Alaska INBRE (Idea Network of Biomedical Research Excellence) and a UAA INNOVATE Award .

"Breakthroughs at UAA in lung cell reactions to tobacco smoke exposure, sister-study

examines smokeless Alaska Native iqmik" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Breakthroughs at UAA in lung cell reactions to tobacco smoke exposure, sister-study

examines smokeless Alaska Native iqmik" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.