Stars are born - and discovered by UAA astronomer

by Kathleen McCoy |

UAA astronomer Travis Rector recently stumbled upon the birth of some stars out near the Big Dipper.

Wait-stuff like this actually happens?

"To be perfectly honest," he wrote in an email, "it's not a major result, but it's a neat discovery and it has a beautiful picture to go with it."

Since when is the birth of baby stars-excuse me, Young Star Objects (YSOs in astronomy-speak)-not news? It certainly had my Monday beat by a long shot.

I joined him in front of a computer monitor to take a look at the starlets and find

out how he'd discovered them.

I joined him in front of a computer monitor to take a look at the starlets and find

out how he'd discovered them.

The image we looked at was originally captured in 2009 through a telescope at Kitt Peak in Arizona. The scene it displayed was ethereal-smoky and blue, with a fierce bright light emanating from the center. Toward the outer edges, star points prick the deep, empty black. It was beautiful and otherworldly.

Officially, this is NGC 7023. Informally, it's the Iris Nebula, so named for its violet and blue color and flower-like shape. Nebula is Latin for cloud, and in this case it's a cluster of dust, hydrogen, helium and other gases that can clump together and give birth to stars.

But this beautiful image is not what the telescope saw, Rector explained.

He pulled up the raw file-exactly what the telescope did see. It included eight rectangular black and white snapshots of the sky, pieced together to create the full image-a dull, gray version of the Iris Nebula.

The telescope doesn't see color, he explained. It simply measures the intensity of light. While the Iris Nebula is as big as our moon, it is very, very faint.

"If you were standing right next to it, you wouldn't see it," he said. That's because the iris of the human eye is just a few millimeters across and takes short exposures very fast. It could never capture such faint light.

The iris for the camera that took the images, on the other hand, is four meters across, or about the size of Rector's UAA office. Exposures take about an hour, per filter.

The filters-red, green and blue-colorize this faint light and allow our human eye to see it.

So, the observatory had emailed him the raw data file of NGC 7023 and asked him to produce an image the human eye could see. It was a nothing-special file, just a chance for another awe-inspiring picture from space.

Rector has a national reputation for creating these. Back in 1997, when he was working

at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, the Hubble Space Telescope was getting

lots of attention for releasing a monthly image from space.

Rector has a national reputation for creating these. Back in 1997, when he was working

at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, the Hubble Space Telescope was getting

lots of attention for releasing a monthly image from space.

A new camera on one of Kitt Peak's telescopes had a field of view about 1,000 times bigger than Hubble, so astronomers there wanted to try making some color images as well. Rector got the assignment. "It'' something I thought I'd do once," he said, "and I've been doing it ever since." Observatories like creating and sharing these impressive images, so taxpayers know what such pricey, publicly owned telescopes are up to.

So, Rector converted NGC 7023's raw data file to something he could load into Photoshop and applied filters that would make faint light visible.

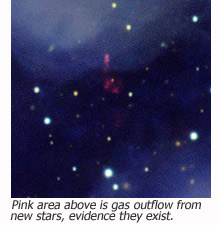

His unique contribution was this: Just for fun, after he'd applied green and blue

filters, he tried a hydrogen alpha filter capable of detecting red light. And that's

when he saw them through an infrared telescope-small, red-colored cloud patches associated

with star births.

His unique contribution was this: Just for fun, after he'd applied green and blue

filters, he tried a hydrogen alpha filter capable of detecting red light. And that's

when he saw them through an infrared telescope-small, red-colored cloud patches associated

with star births.

What he actually saw were the equivalent of star gases, evidence that stars are hatching. Get ready for some astronomy jargon. These are called Herbig-Haro (HH) objects, named after the two guys who recognized in the 1940s that they were distinctive. They form when high velocity jets blast out from newly forming stars and collide with dust and gas. HH objects are "temporary;" in astronomical terms, they last a few thousand years.

Rector picked them out in the image, and then started researching to see if they'd been spotted before. Experts confirmed they had not. The full census of HH objects is only about 1,000, so they are rare enough. His paper on it has been accepted for publication in Astronomical Journal, after which other astronomers who work with stars will check them out.

The thrill for Rector was making a discovery in an area he doesn't even work in. He's a quasar man-the study of very distant galaxies that are very luminous, first discovered in the 1950s and '60s. Much as Darwin's theory of evolution unifies life on Earth, Rector studies and proposes models that might explain all the different types of quasars and how they are related.

Which brings me to my biggest disappointment writing this column about Travis Rector. It's over. And there's so much more to say.

Come back next week for Part II: How to explain the universe to your 4-year-old.

FIND OUT MORE:

- Deep-Sky Images: Find a gallery of Travis Rector's images at his website

- UAA Planetarium: Learn about ongoing programs at this website

- Paper: A Search for Herbig-Haro Objects in NGC 7023 and Barnard 175 (PDF): Rector's paper in the Astronomy Journal

Note: A version of this story ran in the Anchorage Daily News Jan. 20, 2013. The I in this story is Kathleen McCoy, UAA Advancement.

"Stars are born - and discovered by UAA astronomer" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Stars are born - and discovered by UAA astronomer" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.