Don Rearden became a scholar in residence at a whaling museum to research his novel on an enduring whale and its hunters

by Kathleen McCoy |

If you've ever been glued to a "Deadliest Catch" TV episode out in the brutal Bering Sea, novelist Don Rearden plans to snag you with his latest story.

Rearden, who teaches introductory writing at UAA, isn't penning thrillers about chasing king or opilio crab. He's imagined a whale that lived long enough to witness three distinct northern whaling eras: pre-European contact, the New England industrial fleets of the 1800s, and today's Alaska Native subsistence whalers.

The idea for an old, enduring whale as the spine for a story came when scientists dated fragments of ivory and stone-tipped harpoons-discovered in the 1980s and '90s by Alaska Native whalers-to hunting weapons that had fallen out of use by the 1880s.

That assessment backed work by scientists who were aging whales to one and two centuries through amino acids in the lens of their eye. When a Barrow resident mailed 48 frozen whale eyeballs to a Scripps Institute scientist in California, most proved younger than 60 years, except for five older males, aged at 91, 135, 159, 172 and 211 years.

That development set Rearden to pondering what such a hoary old whale might have lived through, from the 1917 'War to End All Wars,' to all the wars that followed. From the arrival of wind-driven whaling fleets to spying submarines. From nuclear blasts at Amchitka in the Aleutians in the late 1960s to Homer's nuclear-free-zone today.

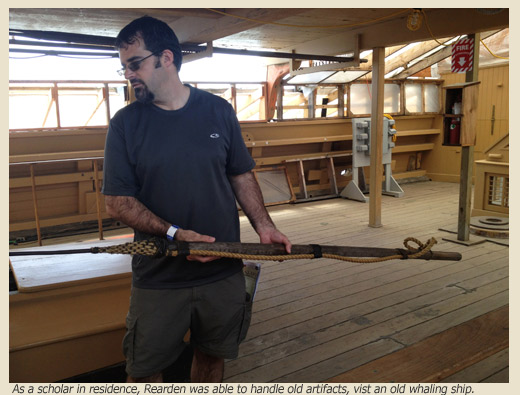

Of course, Rearden needs humans to tell this whale's story. That's why he spent a

week as a scholar in residence at the New Bedford Whaling Museum in Massachusetts

last summer. He credits a creative projects grant from UAA for helping him earn this

status and gain access to original whaling sources and artifacts.

Of course, Rearden needs humans to tell this whale's story. That's why he spent a

week as a scholar in residence at the New Bedford Whaling Museum in Massachusetts

last summer. He credits a creative projects grant from UAA for helping him earn this

status and gain access to original whaling sources and artifacts.

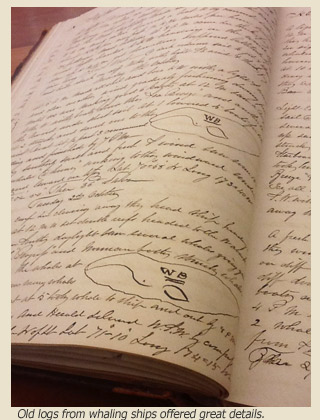

Back east, Rearden poured over spidery entries in ships logs that charted weather, direction, strange sea sightings and more. The Yankee whaling fleets of 1800s usually journeyed from Nantucket or New Bedford, around South America's Cape Horn to the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) for restocking, before heading north into the Bering Sea.

Were they good writers? Sometimes, Rearden says, but often the blunt facts were as compelling as anything he's ever read. Like one log entry, noting an injury to the first mate's hand. Rearden followed the log as the journey progressed.

"A couple of weeks later, the hand is still bad. By four weeks in, there's a meeting with other captains deciding who's going to take the hand. Finally, a captain from another bark (vessel) says he's comfortable doing it, because he's taken a few fingers before...."

Another passage that captured Rearden was a log entry for April 17, 1877 that marked the many troublesome days the Mount Wallaston spent passing through an ocean layered with Portuguese man o' war, their venomous tentacles stretching 20 and 30 feet.

"In some places we sailed through streaks so thick they resembled the bodies of whales

just under the surface," read the log. "At others, we saw the long sinuous tracks

of immense sea serpents..."

Rearden identified with the whalers' fear and wonder. His schoolteacher mother and

law enforcement father brought him to northwest Alaska villages in second grade "I

grew up on the tundra and the rivers," he said. "The sea is strange to me."

Taking breaks from research, Rearden could wander from the archives into the museum

to handle whalers' harpoons, climb into the cramped forecastle of a renovated bark

to see where the crew slept shoulder-to-shoulder, stand in the tiny galley where their

food was prepared and study the red brick ovens that held pots for rendering whale

oil aboard ship.

Taking breaks from research, Rearden could wander from the archives into the museum

to handle whalers' harpoons, climb into the cramped forecastle of a renovated bark

to see where the crew slept shoulder-to-shoulder, stand in the tiny galley where their

food was prepared and study the red brick ovens that held pots for rendering whale

oil aboard ship.

A big surprise for Rearden was noticing the international character of crews that manned these barks. One historical account puts fleet strength at the height of Yankee whaling at 10,000 men, with nearly 3,000 of them being Africans. Many others were Polynesian and Pacific Islanders.

"This is something Alaskans probably don't think about," Rearden says, just how strong the historic pull to the arctic was for global sailors. Rearden has found an account of two Hawaiian seamen who refused to leave a vessel that got stuck in arctic ice. Everyone else departed; as the only eventual survivors, they lived to tell their story to Hawaiian newspapers when they got back home.

That story, and one of a single crewman who wintered over with the Inupiaq people after the great whaling disaster of 1871, are the facts from which Rearden will weave fiction. In that remarkable event, strong winds pushed pack ice toward Alaska's shoreline, locking in some 40 vessels strung along the coast near Wainwright. More than 1,200 people survived, but total economic losses were put at $1.6M. East Coast news accounts about the single survivor report that Inupiaq men wanted to kill him, but Inupiaq women kept him alive. The man reported that he wouldn't do it ever again, not even for $175,000.

In addition to a figure representing the Yankee whaling fleets, Rearden will develop the figure of an ancient, pre-Contact hunter. He's already got a modern Barrow whaler in mind, and hopes for an opportunity to learn more from him about present-day subsistence hunts.

And what of the whale's voice? Can we expect to "hear" from it?

That's very tricky, Rearden said. But his youth in rural Alaska surfaces here. At whaling time in northern villages, everyone was expected to behave well and have "good thoughts," Rearden said, because a whale that heard divisiveness would not give itself to hunters.

Maybe this is a clue to why Rearden's centuries' old whale is still rolling gracefully

through cold arctic waters, waiting.

Note: A version of this story ran in the Anchorage Daily News on Feb. 4, 2013.

"Don Rearden became a scholar in residence at a whaling museum to research his novel

on an enduring whale and its hunters" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Don Rearden became a scholar in residence at a whaling museum to research his novel

on an enduring whale and its hunters" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.