The chocolate gamble: what lab rats can tell us about the power of rewards

by Ted Kincaid |

What motivates you? A paycheck? Chocolate? The question of sustained motivation is

one that interests experimental psychologist Eric Murphy, a professor in the Department

of Psychology. In his 10 years as a professor at UAA, he's worked with students and

colleagues in Alaska and beyond to better understand habituation-the decrease in response

over time to a stimulus-and the implications it may have for addressing the kinds

of overindulgence in humans that can lead to obesity and alcoholism. And he's done

it all with rats.

What motivates you? A paycheck? Chocolate? The question of sustained motivation is

one that interests experimental psychologist Eric Murphy, a professor in the Department

of Psychology. In his 10 years as a professor at UAA, he's worked with students and

colleagues in Alaska and beyond to better understand habituation-the decrease in response

over time to a stimulus-and the implications it may have for addressing the kinds

of overindulgence in humans that can lead to obesity and alcoholism. And he's done

it all with rats.

A typical day at the office for Earl, a Wistar lab rat in UAA's Department of Psychology, involves a short commute to the operant conditioning lab (about 25 feet away from his home) for work in a Skinner box where, if he presses a lever under the right conditions, he's rewarded with chocolate pellets. Sound like your job?

That lever press is a learned response that acts as a quantifiable placeholder for behavioral researchers. Professor Murphy and his students aren't really interested in the lever-pressing, in and of itself, but they care that the rat can learn a behavior and adapt that behavior to different conditions. The rats learn consequences of their actions. If I push this thing here, a tasty treat comes out over there.

Operant conditioning, an approach used by Professor Murphy and his team, is learned behavior modified by consequences. While the term "consequences" has a negative connotation for most people, the Murphy lab researchers deal in positive consequences-learn something, get a food pellet.

Professor Murphy notes that it has been well-documented in research across animal species that the power of a reward-like a chocolate pellet or a drink of alcohol-to motivate a subject changes in both the short and long term, from a single session in a Skinner box to repeated sessions over a number of weeks or months. So the research he's doing with students and with colleagues currently focuses on manipulating this mercurial interest level or habituation, in rats. The implications for both animal research and human behavioral research are intriguing.

"If what we're looking at is habituation, how can we increase the efficacy of a food reinforcer or decrease the efficacy of a food reinforcer?" asks Professor Murphy. The answer is short: keep 'em guessing.

What are the rats telling us?

What are the rats telling us?

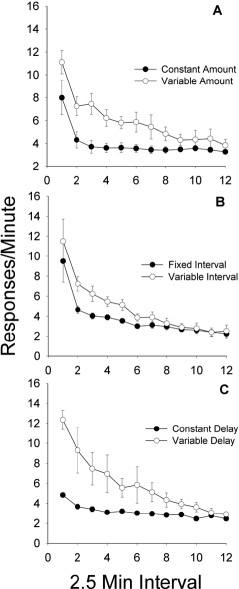

Even a quick glance at the graphs at right showing Professor Murphy's data is telling-two disparate paths to similar endpoints. Varying the amount (how many pellets the rats receive for a lever press from one to nine pellets vs. a consistent five pellets), varying the interval (how often the lever can be pressed to produce a food reward, from one to 23 seconds vs. every eight seconds) and varying the immediacy of response (how long the rats must wait after pressing the lever to receive their reward, from one to 19 seconds vs. a consistent reward every 10 seconds) keeps the rats more engaged in reward-seeking behavior.

"When you think about food motivation in humans, if we can isolate some of the factors that contribute to a person's motivation to eat, we might be able to tackle one dimension to that problem," says Professor Murphy. "What my rats are telling me is that the more constant the food is, the less interested they are in eating it."

But mix it up a bit so they're unsure-when? how much?-and they'll more aggressively seek the reward. "It's like gambling when you think about it," says Professor Murphy.

"I should note that the amount of food delivered in each of these experiments is the same," he says.

Make the leap to human behavior and it just might explain "the thrill of the chase" that drives trophy hunters, bargain shoppers and aspirational daters.

Student involvement in research

Mikal Milton is the colony manager for the Wistar rats like Earl, the Long-Evans rats and the Siberian dwarf hamsters used by students and professors in the Department of Psychology to study animal behaviors. Though the hamsters are cute, she's a little partial to the rats, suckers that they are for belly rubs. According to Mikal and Professor Murphy, they can be sweet, funny and clever, or, like one rat's cage nameplate brands him, "a slow learner." She's been working with the animals for two years and, while maintaining a spot on the Dean's List, is just five credits away from earning her bachelor's degree.

She's in the lab most days. "I know most of them by name," she says of the animals. There's Rupert, Bojangus, Franco, Ferdinand and Gus, just to name a few. "I've been here on Christmas." But, if anything, the hands-on experience caring for the animals has strengthened her attachment to the lab and to UAA. "Eventually I'd like to come back here and teach. I want his job," she says with a laugh, pointing at Professor Murphy.

But it looks as though he's not going to give it up without a fight. "You have to

wait 20, 25 years, then," he says, matching her laugh. A UAA alum himself, he earned

his undergraduate degree in 1998 before heading to Washington State University for

his Ph.D.

But it looks as though he's not going to give it up without a fight. "You have to

wait 20, 25 years, then," he says, matching her laugh. A UAA alum himself, he earned

his undergraduate degree in 1998 before heading to Washington State University for

his Ph.D.

Alaska and UAA drew him back in 2003 and he's been working with undergraduate students and researchers ever since, involving them in habituation research and overseeing projects.

Students in his Learning and Cognition class each semester are assigned a rat and are charged with training their animal using operant conditioning. Some of them approach the assignment with trepidation.

"Once a student actually starts working with the rats, they see they're like small dogs. Highly trainable, intelligent, social, affectionate," Professor Murphy says. "Students immediately get hooked." That early exposure has parlayed into more than one undergraduate research project through the UAA Honors College. Experience in the Murphy lab has also propelled some students on to careers in biomedical and behavior analysis fields.

"My first Honors student is now a surgeon in Seattle," he says.

In August, he welcomed his first graduate student to the Murphy lab: Whitney Bakarich. She arrived at UAA from Colorado with some years of clinical experience under her belt. Her thesis will be centered around rat research in the operant conditioning lab. It will be UAA's first rat lab master's thesis in 30 years, Professor Murphy notes.

Connecting the research-Habituation, obesity and autism

Professor Murphy has a book coming out soon from scientific and scholarly publisher Wiley-Blackwell, co-edited by his long-time collaborator from Washington State University.

"It's one of those big books that probably no one will ever read," he says with a grin. Their work has actually already caught the notice of a researcher in Buffalo, New York, who is applying some of the concepts laid out in Professor Murphy's publications to his work with obese kids with some early success.

There's potential for further collaborative study, too. Professor Murphy and the Buffalo researcher have noticed that there are differences in the rate of habituation between individuals across species. The Buffalo researcher has noticed that people who habituate slower-or take longer to lose interest in rewards-tend to eat more food and be obese. Professor Murphy has noticed the same thing in the lab rat colony and is interested in taking a look at individual rat habituation curves soon. Any undergraduate research hopefuls up to the challenge?

The Murphy lab research might also have implications for the treatment of autism. Positive reinforcers are recognized as crucial to behavioral treatment with children on the autism spectrum and recommended by the American Medical Association. Understanding how to maintain the efficacy of positive reinforcers during treatment sessions with children who have autism could help improve therapy sessions and the everyday lives of parents to children with autism.

That's the importance of animal behavior modeling in the hands of a dedicated researcher like Professor Murphy. Who needs a chocolate?

"The chocolate gamble: what lab rats can tell us about the power of rewards" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"The chocolate gamble: what lab rats can tell us about the power of rewards" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.