Chevak teacher aides on the path to becoming fully qualified classroom teachers through UAA's College of Education

by Kathleen McCoy |

Here's a fact for you: 70 percent of Alaska's schoolteachers come from out of state. They arrive from Minnesota or California or Michigan, and struggle to settle in to village Alaska where they find jobs.

That constant rotation is hard. Short-term teachers rarely feel part of the village, and the village never fully embraces them. And students can pay for the disconnect; rural Alaska schools post some of the lowest achievement scores in the state.

The village of Chevak, home to almost 1000 residents and 250 school children. This village has a single-site school district because of its Cup'ik cultural and language heritage. For more than 30 years, the village has hoped and worked toward a K-12 Cup'ik immersion school. Currently it offers that program for K-3. (Photo by Sheila Sellers, UAA)

It's not a big leap to imagine the benefits of teachers rising right out of the villages, where they know, live and value the local ways. A program to make that happen is underway in Chevak, a Cup'ik community along the Kashunak River in Western Alaska, with 1,000 residents and 250 school children. A cohort of more than a dozen Chevak teacher aides are now on the path to becoming fully credentialed classroom teachers.

Because the community speaks a dialect of Central Yup'ik, called Cup'ik (pronounced Chew-pick), it was able to create the one-school Kashunmiut School District with a local school board.

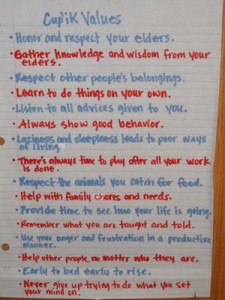

Elders in the village, John Pingayak, David Boyscout and others, had a vision for the school they wanted. It would be "like two rivers flowing together, one western and one Cup'ik." Neither would dominate, and both would best prepare their children to thrive in a fast-changing world while remaining rooted in their own culture.

For years, the community has cultivated this dream, a K-12 Cup'ik language immersion school. They have succeeded through the third grade, but teacher turnover takes a toll here, too. Plus, new teachers don't arrive speaking Cup'ik. How could they ever fulfill the goal of a Cup'ik immersion K-12?

About three years ago, a superintendent, Les Kramer, recognized the stability and cultural strength the teacher aides represent. They already speak Cup'ik. They are raising their families and deeply rooted in the community and its culture. Why couldn't they become the school's fully credentialed teachers?

Kramer called UAA's College of Education and asked how it could happen. The answer wasn't obvious, but together the college and the district began to explore the possibility. In 2010, a handful of education professors traveled to Chevak and sat in the school library listening to teacher aides describe their drive to become fully qualified teachers. Many of them had already worked 10-15 years at the school.

Three years later, eight of the cohort are poised to receive their associate of arts degree in December 2013; many want to continue on for a bachelor's degree in elementary education.

The journey from then to now took place almost exclusively in Chevak, with education professors flying in for 10-day stints, followed by online learning as students settled into coursework. Students were able to fit college classes around their school jobs and family obligations right in Chevak.

From the beginning, the school and the university shared a commitment to draw from western education theory and practice and Cup'ik knowledge and sense of place. Exactly how to do that was an ongoing discovery, but Nancy Boxler, one of the liaisons to the cohort, says the process is transformative, both for the school and the university.

This session followed a 2010 workshop with Sheila Sellers from UAA's College of Education as she presented Western theories of childhood development. The students followed with presentations that reflected Cup'ik values and their relationship to childhood growth and development. Pictured here (l-r) are Elsie Ayuluk, Cora Charles and Mary Matchian. (Photo by Sheila Sellers, UAA)

Irasema Ortega, an assistant professor of science education, can tell part of that story. Last summer, she headed to the village with colleague Cathy Coulter, an associate professor of elementary education, to spend a week with the school's teachers creating an elementary science curriculum that would include STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) skills.

The team writing the science curriculum was inspired by ways people in Chevak talk about nature's abundance and value. One lesson plan on building graphs incorporated subsistence. The assignment for students became finding out how many gallons of blueberries their extended family gathered and stored for winter. In the case of subsistence food, elders receive theirs first, so the curriculum committee built that into the equation, too.

"Subsistence goes beyond just going to fish camp or collecting berries or moose hunting," said Coulter. "It is a way of living and taking care of each other." The Anchorage professors say they will take ideas like this back to their elementary education classes at UAA to show how sense of place can be built into all curricula.

All of this takes money. One superintendent applied temporary federal stimulus dollars to support the project. It also got a financial kickstart from Anchorage businessman Barney Gottstein, a previous longtime member of the state school board. While serving, he became convinced by the vision Tlingit educator Bill Demmert had for how to teach Alaska Native children: Put an Alaska Native teacher in front of them. When Gottstein saw an opportunity to support that vision, he did.

The Chevak cohort, which has named itself "Cup'ik Dream," recently paid a visit to Anchorage to present at an indigenous education conference. In bright-colored kuspuks, they filled a panel at the front of a classroom, speaking mostly of their commitment to finishing what they have started: Becoming fully qualified elementary schoolteachers in Chevak.

Susie Friday-Tall, seven years the secretary at the school and now studying to be a teacher, opened the panel with a piece of driftwood in her hand, to be shared as each panelist spoke.

She said her mother always told her that when she came upon a piece of driftwood, she must turn it over. The driftwood would thank her, so the lesson went, because it needed turning, having been stuck on one side for so long.

For the professors and students in Chevak, that story seems a useful metaphor for the change rural school systems in Alaska need. They, too, have been stuck on one side for a long time.

NOTE: A version of this story ran April 14, 2013 in the Anchorage Daily News.

"Chevak teacher aides on the path to becoming fully qualified classroom teachers through

UAA's College of Education" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Chevak teacher aides on the path to becoming fully qualified classroom teachers through

UAA's College of Education" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.