UAA 2013 Campus Master Plan reflects added research initiatives, changing student body

by Kathleen McCoy |

University land use plans are hardly known for riveting plot turns and reader claims of "I just couldn't put it down!"

Yet the newest plan for UAA is worth a look, for early signs of how the campus will grow, and a visual history of how far it has come. Four Alaskans and an architect from Seattle, aided by 25 volunteer faculty, staff and students, reworked the plan over the past year. On Friday, Sept. 27, 2013, the University of Alaska Board of Regents endorsed the plan at their Juneau meeting.

What started as an update to a 2004 document (refreshed once in 2009) morphed into a granular analysis of how users interact with the current campus. There were surprises.

Earlier master plans were written for a commuter community college that only later in life added a university. Now it has graduate degrees in health, engineering and business, with demand for higher-level facilities.

"I think UAA grew up," said team leader and architect Brian Meissner of ECI/Hyer, "and our work came on the heels of that."

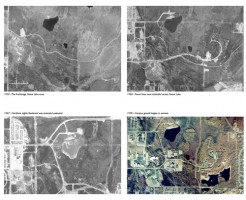

Over the same decade, the university's neighborhood grew up. As ink dries on the 2013 campus plan, the U-Med District fires up its own master planning process. (View larger versions of the eight images on this page by downloading a copy [90-page PDF] of the 2013 UAA Campus Master Plan. History appears on Pages 82-86.)

Simultaneously, the municipality and state continue to pursue a new northern access route into the area. Because UAA's plan was first off the blocks, and because the northern access debate is beyond its scope and authority, the campus plan accommodates either scenario-a new road in, or the status quo.

Meissner and Jason Swift of ECI/Hyer, urban planner Wende Wilber of CRW Engineering, Peter Briggs, landscape architect from Corvus Design, and Allyn Stellmacher of ZGF Architects of Seattle, all partnered with Lonnie Mansell, UAA's facilities planner. Kittelson & Associates concentrated on traffic.

Their work last fall started with extensive listening sessions among staff, faculty and students that updated how the present-day campus is used.

"There's been a shift away from a commuter campus to a semi-commuter campus," Meissner said, meaning today's commuters go fulltime and behave more like dorm residents. Instead of dashing in for a single class, they stay all day. They take a class, study at the library, get some exercise in the gym, grab food and head back to class.

If they can't get a brick-and-mortar class to fill their schedule, they're in the library or sitting along the campus spines, signed into their online courses. Some have schedules split 50-50 between physical and virtual classrooms.

"They aren't at home in fuzzy slippers," Mansell said. "They're here, all day. We've had to upgrade the campus bandwidth just to accommodate the volume," as well as formalize more settings for students to study and congregate.

Another finding: Because they come and stay all day, students told planners they don't mind leaving their cars in peripheral garages. Having a more dense campus that is easy and pleasant to move through-out-of-doors on foot or bike-is more appealing than parking two minutes from class.

That means campus pathways need work. Right now, south-side walking paths hiccup with broken or missing connections. On the north side, an attractive wooded route along Chester Creek stops abruptly at UAA Drive. While the "urban campus set in nature" remains UAA's chief physical asset, Meissner said, that busy asphalt road slicing campus persists as its Achilles heel.

Over the next decade, watch UAA fill in or "densify," with parking garages on the edges and separate perimeter routes for cars and shuttles, bikers and walkers.

Expect more skyways crossing Providence Drive to link UAA buildings on each side and a pedestrian/bike tunnel beneath UAA Drive. If a new northern access road ever opens east of campus, planners strongly recommend closing at least part of UAA Drive to cars as a way to solidify campus cohesion.

UAA's stewardship of its campus forests has for three years earned it national Tree Campus status; for any tree removed, another is planted.

Yet, aerials from the 1970s and '80s show a campus that could more accurately be called "the parking lot campus." This master plan replaces those expansive, gray lots with eventual new buildings; the engineering one rising in the old Wells Fargo Sports Complex lot is an example.

Cultivating an "urban campus in a natural setting" will be much easier as those lots disappear, Meissner said, replaced by better-landscaped buildings and adjoining green space.

Another innovation in this plan is intentionally raising the profile of campus-community gateways at UAA's east, south, north and west borders. Now they will be called "community interface zones" especially primed for public-private partnerships, the commercial amenities that both community and campus can enjoy.

What do you see on the fringe of most urban college campuses? Coffee shops, copy services, restaurants, pubs, new and used bookstores, art stores, mixed residential units over commercial space, even small research centers.

University leaders say they plan to nurture these "front doors," creating an environment where Anchorage and campus mingle more easily. It adds up to a coming of age for Anchorage's young university.

Note to readers: A version of this story by Kathleen McCoy ran in the Sept. 29, 2013 edition of the Anchorage Daily News.

"UAA 2013 Campus Master Plan reflects added research initiatives, changing student

body" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"UAA 2013 Campus Master Plan reflects added research initiatives, changing student

body" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.