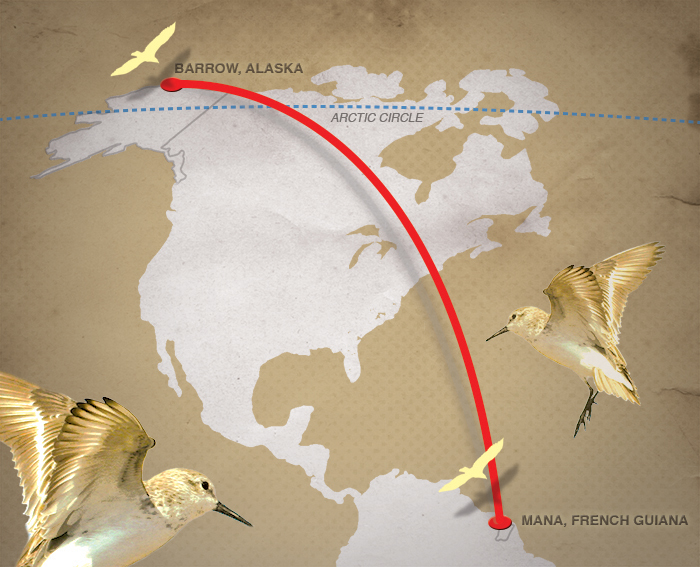

One bird, 6,000-mile migration

by Jamie Gonzales |

It's a small world. That's the refrain that comes to mind when you hear Audrey Taylor's story about a very small, continent-hopping bird.

Several years go, Taylor captured and tagged a shorebird, a Semipalmated Sandpiper, in Barrow, Alaska, as part of her ongoing shorebird research. Four years later that tagged bird showed up in French Guiana, confirming scientists' hypotheses of that particular species following that particular far-flung path. It established a link between breeding grounds in Alaska's Arctic and winter habitat in Northeastern South America.

Just last month, Taylor, now an assistant professor of environmental studies at UAA, made her own Alaska to French Guiana trek and met the man who'd spotted "her" bird, one of some two million Semipalmated Sandpipers in the world, and it reminded her yet again of the complexity of the puzzle she's trying to solve.

"You see birds breeding in Alaska and you have no idea what happens to them in the non-breeding season, but all of the things that we do to our environment in all the places the birds stop between winter and summer potentially has an impact on these birds," she says.

Taylor is working with a network of scientists and conservation groups across North and South America to gather data that paints a full picture of the lifecycle of these highly migratory birds.

Shorebird hunting in French Guiana

To someone from Alaska, land of giant animals, shooting a tiny shorebird for meat or sport may seem odd, but the shorebird wintering grounds in South America are home to several different bird-hunting groups.

Taylor's most recent research, funded by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory Bird Management, is a two-year project that will take her to French Guiana to meet and observe hunters and try to gather baseline data about shorebirds overwintering there.

"It's going to be difficult to do, but we're trying to assess how much impact hunting has on these populations," Taylor says.

Her September fact-finding visit to Mana, French Guiana, helped her get the lay of the land. She was able to meet with the leader of one of the hunting groups in the area, who lined out three types of hunters for Taylor.

"One is really subsistence, one is coming from the big city and they just do it as a kind of get-out-in-the-country-and-blast-away-at-things and one group is local hunters who do it more for fun, probably like a lot of people in Anchorage who go to the surrounding areas of the Kenai Peninsula or up toward the Interior and hunt for the purpose of getting meat and also because it's fun to get out in your local environment," she says.

Target species or unlucky bystanders?

Assistant Professor Audrey Taylor in the field with another shorebird species, a Red-necked Phalarope.

Also like Alaska, there is a little tension between groups after the same resource. But that tension has brought about the first glimmers of interest in resource management, which is a big deal for a place like French Guiana-officially an overseas region of France-with zero game management and an "anything goes" culture surrounding hunting.

Taylor says their theory is hunters are targeting Lesser Yellowlegs, a slightly larger shorebird whose population is declining precipitously, but the imprecision of shotgun birdshot ends up killing other species like the Semipalmated Sandpipers, who have the unlucky habit of flying and foraging beside the larger birds. So what happens to the sandpiper casualties?

"That's something we don't know," says Taylor. "If [hunters] get a bunch of Semipalmated Sandpipers, do they collect them and eat them or sell them or just leave them on the ground?"

Taylor and her co-collaborators will plan to observe and talk with hunters over the next two years.

On her next trip to Mana-a two-week trip in January between teaching responsibilities-Taylor will be accompanied by a UAA alumna, Eve Van Dommelen (B.A. Languages '13), a fluent French speaker who will assist with translation.

"What we'll do is try to station ourselves at the rice field-this big open area where they're hunting the birds that come in to these pond areas. We'll station ourselves out there and watch as people come in," says Taylor. "People are really friendly. We'll try to go talk to them and ascertain what group they're from."

Life is a flyway

Management of migratory species like birds and fish is often a multi-agency, international collaboration. For birds, one management strategy has been to group birds in "flyways."

Similar to time zones, there are four American flyways-Pacific, Central, Mississippi and Atlantic. Four flyway councils are convened to help sort out the management of border-hopping bird species.

Most Semipalmated Sandpipers follow routes along the Atlantic Flyway, stopping to rest and eat on their 6,000-mile migration where they can. In particular, they try to pack in the calories before those long stretches over open ocean.

"It's an interesting time to be working on shorebirds," says Taylor. "People are finally starting to realize there are all these migratory connections and they're not just our birds, they're other people's birds, too."

Understanding the data

Here's a little Taylor trivia. This summer, Taylor wrote a thank-you letter to the Anchorage Police Department that got picked up by the news. In it, she praised the heroics of two local police officers who she flagged down to help her rescue errant ducklings that had fallen into a storm drain along Minnesota Drive.

So, truth time, how tough will it be for a duckling-saving ecologist to observe the hunting of several bird species she is working to protect?

Taylor laughs a little at the question. "It'll be a challenge," she agrees. "But by the same token, I feel like it's really powerful when you realize why people hunt and their connection to that animal comes from a very different perspective than mine does, but it's still a connection that deserves to be recognized."

Once her team is able to collect the data and analyze it in the larger context among other data showing the impact of hunting on shorebirds in South America, they'll have a better idea on how to proceed with management conversations.

"If hunters are hunting for food, then that's a different scenario than if they're just doing it for sport," says Taylor. "Education would have a different impact vs. extra policing."

But are the people of French Guiana ready for game management strategies?

"I think the local [hunting] group is," she says, "because they're seeing an impact from off-the-radar subsistence hunters and the big city people coming in. They perceive the birds there locally as their resource."

Taylor will also be working with a local conservation group called GEPOG, Group for the Study and Protection of the Birds of French Guiana.

The locals recognize that by establishing even minimal management, maybe licenses for hunters, they'll at least know who and how many are after the same resources.

Taylor's project is just one important step in that direction.

"One bird, 6,000-mile migration" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"One bird, 6,000-mile migration" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.