Envisioning new transportation routes in the Arctic

by Kathleen McCoy |

Will the Arctic turn out to be Alaska's post-Prudhoe Bay salvation? Or will Russia and Norway somehow beat us to the punch?

Andrew Metzger focuses on probability-based engineering design, leading him to envision a transportation corridor in northwest Alaska that could help get oil and mining resources to market. Here, he ascends a ladder after adding instruments to the Auke Bay ferry terminal in Juneau, used to measure vessel impact forces on the dock structure. Photo by Jonathan Hutchinson.

No one knows, but what's clear is transportation in the Arctic is developing and a corridor along the northwest coast could make a difference in Alaska's economic future.

It comes from Andrew Metzger, a civil engineering professor at UAA. For the past four years he's been pondering the challenges and opportunities around Arctic infrastructure-think offshore oil development, shipping, ports and harbors and moving natural resources to market.

Two Arctic transportation corridors already exist-the Northwest Passage along the coast of North America connecting the Atlantic with the Pacific, and the Northern Sea Route from Murmansk in the Barents Sea, along Siberia, to the Bering Strait and Far East.

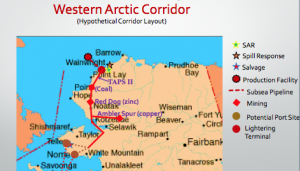

Metzger's vision for a Western Arctic Corridor would connect oil resources on the North Slope to coal, copper and zinc resources and help ship them through a western Alaska port. Image provided by Andrew Metzger.

Russia and Norway already have invested heavily in the Northern Sea Route (Metzger calls those two countries the real "movers and shakers" in the Arctic, well ahead of Canada and the U.S.)

But according to Metzger, who spends lots of time at Arctic policy conferences here and in Washington, shipping won't boom in the Arctic immediately for a couple of reasons.

First, there's a lack of search and rescue and salvage capabilities along the routes. These services will be necessary for insurance companies to confidently underwrite Arctic voyages. Additionally, these routes have areas of shallow water. That fact decreases the volume-per-vessel capacity than is possible, say, through the Suez Canal.

One way to get Arctic offshore oil to market is bringing it over to Prudhoe Bay and down the TAPS pipeline. But Metzger has another path in mind, an elevated rail/pipeline system starting near the Arctic offshore lease areas, running down the west coast through known and rich mining districts, all the way to Nome, where oil and other resources would head out to the world.

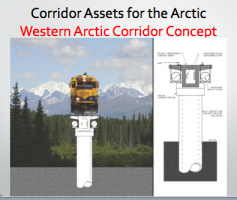

A rendering of what the elevated rail/pipeline transportation might look like. Image created by Hollace Metzger.

Rail cars would carry dry-bulk cargo, such as mining products. Pipelines would convey fluid cargo (oil from the lease area and potentially natural gas). "If you had a natural gas power plant on the North Slope, you might be able to wean the whole region off of diesel," Metzger says. "And those trains? They could be electric."

Within the hollow girder supporting the rail, he'd allow channels for power and communication. A fiber optic cable project due to link London to Tokyo through the Northwest Passage by the end of 2014 could use this corridor to connect northern Alaska coastal communities with areas in the Interior.

He calls it the Western Arctic Corridor, and even he calls it radical. But probability-based engineering design is his area, and "technically speaking, this could be feasible."

It's elevated because railways scar landscape and interfere with wildlife. He'd run the rail up on circular concrete girders drilled 60-100 feet into the ground, well past heaving permafrost. The entire system could be built from atop these elevated platforms, segment by segment. The technique has been used successfully to build bridges over sensitive habitat. Only survey and the geotechnical engineering crews have to work on the ground.

OK, so how to pay for this grand scheme? Customers, says Metzger, a blend of public and private interested parties.

"Transportation systems exist to provide service to customers. So the first step is to identify them. Next, look at specific corridors within the system. Corridors provide levels of service required by customers. Once you know the type and level of service they need, what needs to be built where becomes apparent."

The $64 million question: Who needs what service?

Likely customers include oil and gas moving crude to market from Arctic offshore leases; miners moving coal from deposits in the Brooks Range, zinc from Red Dog and copper from Ambler. Then there's the federal government missions of coastline security and public and environmental safety with the Coast Guard, seafloor mapping with NOAA and ongoing work by agencies like the NSF and the Department of Interior. China and Japan have expressed interest in this region, too, Metzger says, and could be considered potential corridor customers.

"The point is, if you're thoughtful about how you route the corridor, you can pull in paying customers all along the way. Now you have a customer base that can pay for the corridor, but also generate revenue on an annual basis."

A version of this column by Kathleen McCoy appeared in the Anchorage Daily News on March 30, 2014.

"Envisioning new transportation routes in the Arctic" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Envisioning new transportation routes in the Arctic" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.