Helping kids build bridges to engineering

by Tracy Kalytiak |

Three girls worked, intent, on a bridge design they needed to perfect and finish before the room full of UAA Summer Engineering Academy students dispersed for an outdoor lunch.

Hannah Romberg, 14, works on a balsa bridge at a UAA summer engineering academy. Photo by Theodore Kincaid/University of Alaska Anchorage.

Ashley Smith, 11, guided a wood-handled saw into slits of a small metal box and sliced sticks of balsa wood while Kathryn Tunnell, 11, squeezed tiny dots of superglue on the balsa. Kristina Yu, 12, carefully tapped and pressed together the balsa pieces in a pattern the girls had sketched out.

The "structure" segment of the week-long "Structure Destruction" summer academy session involves planning and assembling 8-inch-long bridges.

The girls explained the "destruction" slated to take place:

"In the bridge competition, they put the bridge on a wood plank and smash it to see whose is most efficient," Kristina said.

"That means the one that stays together," Kathryn said. "I think that's going to be somebody else's."

"Not ours," Kristina agreed.

"All this work and it's going to break," Kathryn said.

Tasting different flavors of engineering

"Structure Destruction" kicked off this year's academy sessions, on June 9. UAA engineering students help the academies' director, Dr. Scott Hamel, by assisting with hands-on tasks and channeling the middle- and high-school students from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m., Monday through Friday, through each session's work periods and breaks for (free) lunch.

Dr. Scott Hamel directs UAA's Summer Engineering Academies. Here, he instructs kids about bridge building. Photo by Theodore Kincaid/University of Alaska Anchorage.

UAA has presented the academies every summer since 2010, Hamel said. UAA faculty devised the sessions, which give students a sampling of programs in UAA's College of Engineering-including civil engineering, geomatics, electrical engineering, mechanical engineering and computer science. The academies continue through Aug. 8 and include instruction in bridge engineering, robotics, 3D modeling, energy, gears and sprockets, and Java programming.

The Alaska Native Science and Engineering Program also convenes a camp for middle-school children, but the two programs do not interact, Hamel said. "ANSEP is a long-term program," he said. "Our purpose is exposure. It's our job to take kids who haven't been exposed to science and engineering and say, 'Hey, here's engineering. It's fun!' That's our primary objective."

The academies are wildly popular, Hamel said, gesturing toward a tall, neat stack of registration paperwork. Approximately 300 children are scheduled for the sessions, all of which are full. Four hundred children applied.

A lottery now determines which students made it into the BP-sponsored sessions. The cost to parents this year was $100; applicants could request fee waivers if they couldn't afford to pay, Hamel said. The most popular sessions? Robotics, Java and Structure Destruction; Robotics' waitlist hovers somewhere between 40-50 people, Hamel said.

Camille Fulton, Kristina Yu, Victoria Roach, Ashley Smith, Hannah Romberg and Kathryn Tunnell take a lunch break at UAA's summer engineering academy. Photo by Tracy Kalytiak/University of Alaska Anchorage.

Girls make up half the participants in the academies' middle school sessions, overall. Eighty percent of those participating in the high school sessions, however, are boys.

Zakary Stone, 22, a computer systems engineering student at UAA, assisted at the academies for the last two years. Bridges are evaluated not only by how long the balsa structures resist the crush of an electro-mechanical press against an I-beam, but by how lightweight the bridge is, Zakary said.

"You divide the load [the bridge] holds by its weight," Zakary said. He picked up one trio's creation and pointed at a "road" the kids had built on the span. "This one uses a lot of wood in making a road. A lot of kids think they need a road, but they don't for these bridges."

Zakary paused when Hamel asked for attention. The professor held aloft two perky little balsa birdhouses, gathered the kids near the press and passed out safety glasses. "Are you ready for this house to be crushed?" he asked. The kids gleefully responded: "Yes!" The metal plate of the press descended toward the peaked roof of the two-hole birdhouse.

One side of the peak snapped, then the other, before the press flattened the roof. A few seconds later, the relentless press forced apart the balsa corners of the house. Each wall bulged, folded and finally, with a resounding "SNAP," collapsed almost flat beneath the press' 994 pounds of force. Afterward, Zakary said he tries to help students understand why their bridges break by pointing out the weak and strong points of their designs. "It's good for everyone to see," he said.

Luke Bredar, Jack Dittrich and Zach Jones display their creations at the "Structure Destruction" summer engineering academy at UAA. Photo by Ted Kincaid/University of Alaska Anchorage.

Asked which of the bridges-in-progress appeared most likely to meet the criteria of being both strong and lightweight, Zakary scanned the room and then pointed to a table where a second trio of girls was sitting down.

Honing new skills

Victoria Roach, 13, Camille Fulton, 12, and Hannah Romberg, 14, sketched their bridge's top and bottom views on the paper-covered table and used the sketches as templates for measuring, cutting and laying out their pieces of balsa.

"We did the exact measurements we would do for the wood so we could put it on top and line it up with the lines," Victoria said.

"We made the top first and then we made our two sides and then we connected it all," said Hannah, who's about to enter ninth grade at West High. "I've done similar projects at school and realized the simplest designs are probably the best."

Then, she pointed out features of their bridge. "We put pieces of wood on top of each other, here," Hannah said. "Putting pressure here," she continued, pointing to a glue joint, "is going to smash it, but if you put pressure here," she pointed to a place where sticks overlapped, "it would just smush the wood."

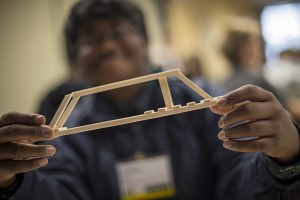

James Tatum shows his balsa bridge at "Structure Destruction" summer engineering academy at UAA. Photo by Theodore Kincaid/University of Alaska Anchorage.

"It took us, like, ages to get these pieces in place because they just keep falling off-more glue, and more glue," Victoria laughed.

The girls didn't construct a "road surface" on their bridge.

"If we would have already had in our heads that we were going to do the road on the bottom, we would have used a lot less wood for the structure itself," Victoria said.

"The structure is the important part-we're not actually driving cars over it, we're just putting the weight on top," Hannah added. "It would be different if this was an actual bridge. For this bridge, we knew we wanted to use triangles."

"I think the ones that have triangles are going to do pretty well, but that one over there with all the squares," Victoria said, pointing at a bridge on another table, "when you press down on top of it, they tend to fall over and they don't evenly distribute the weight."

The academy students marveled at video of an event that's been called the most dramatic failure in bridge-engineering history-the dramatic collapse of the four-month-old Tacoma Narrows suspension bridge during a Nov. 7, 1940, windstorm. Hamel used the video of the twisting, rippling, bouncing bridge as a springboard into discussion of what happened to it, why it collapsed, how the collapse taught engineers how to create stronger, more secure bridges.

Ashley Smith sits near a balsa bridge she helped build. Photo by Theodore Kincaid/University of Alaska Anchorage.

"There are lots of bridges with wires that help hold them up, but they have more support underneath," Kathryn Tunnell said, later. "The Tacoma Narrows had half a mile between both poles."

"The weather made it weak," Kristina Yu said. "It started swaying like a seesaw." "That was crazy!" Victoria said of that video.

Camille wanted to attend the academy because she likes building things-she's built bridges before, using straws and masking tape. Her brother attends high school in Eagle River.

"He brought home a paper about this and we found out there was a program for me," the Gruening Middle School student said.

Victoria came to the academy unexpectedly; the homeschooler's name had been parked on a waitlist until a week ago.

"I like building things, and the name 'Structure Destruction' drew me in," she said. "It's kind of sad our pretty little bridge has to be smashed."

Written by Tracy Kalytiak, UAA Office of University Advancement

"Helping kids build bridges to engineering" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Helping kids build bridges to engineering" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.