Reviving Inuit identity through ink

by joey |

Holly Mititquq Nordlum, B.F.A. '04, recently received a Time Warner Fellowship from the Sundance Institute to continue her documentary work on Inuit tattooing. (Photo by Phil Hall / University of Alaska Anchorage)

A version of this story appeared in First Alaskans magazine, winter 2016 issue.

For hundreds of generations, Inuit women across the Arctic tattooed patterned lines, frequently on the chin, that identified their status in the community. Though colonial pressures of the past century disrupted the cultural practice, the gap is fresh.

According to Anchorage artist Holly Mititquq Nordlum, now filming a documentary on the subject, the majority of Alaska's Inuit women-including her great-grandmother-were tattooed as recently as three generations ago. She's hoping to continue the tradition, and she's not alone.

The simple lined designs, originally applied via soot and sinew, can be quickly completed with a modern tattoo machine. But the intimacy of hand-poking and skin-stitching provides time to discuss connections to the past and stigmas of the present. Physically, the end result is an upfront, indelible and permanent connection to heritage. Spiritually, the tattoo builds a direct connection to generations of powerful women. That's the story she hope to share in her upcoming documentary.

In August, Nordlum received a Time Warner fellowship from Utah's Sundance Institute to support her film project, Tupik Mi. The brand-name recognition was the latest break in a massive project for Nordlum, connecting her with industry players like HBO and Netflix as she works to continue filming her project. And while the pursuit of funding feels like a full-time job, she's still passionately pursuing the film's subject. As an Inupiaq woman from Kotzebue, recording and reviving the fading art of Inuit female face tattooing is incredibly close to home.

Tattooing threads artists across the Arctic

Nordlum received her tattoo in 2015 during a Polar Lab event sponsored by Anchorage Museum. (Photo by Michael Conti / Anchorage Museum)

Though Nordlum's worked as an artist for more than a decade, this project is her first foray into film. A visiting printmaker at her Kotzebue junior high first inspired her to become an artist. "All it took for me was one guy making it fun," she recalled. But that interest didn't become a career until enrolling at University of Alaska Anchorage. "I didn't have the confidence to just say [I was an artist]," she recalled of faculty support.

After earning a fine arts degree in 2004, she launched her graphic design business, Naniq Design, and began collaborating on art education with Anchorage School District, aiming to inspire the next generation of Alaska Native artists. Her work can be seen across the city (currently, in a poster series at Anchorage Museum, a gallery show at Middle Way Café, and soon on large metal panes at the city's main library) but the Sundance fellowship, plus funding from Alaska Humanities Forum, has allowed Nordlum a little more freedom to focus on her documentary, which she calls "all-consuming."

The project started thanks, in part, to Facebook. While searching for someone to tattoo her own chin, Nordlum connected online with Copenhagen-based Maya Sialuk Jacobsen, a Greenlandic Inuit tattoo artist researching the vanishing artform. Through support from the Anchorage Museum, Jacobsen visited in 2015 to host an educational symposium and perform her first skin-stitching tattoo on Nordlum.

That initial meeting spurred a much larger project. Alaska Public Media's coverage of the tattooing event went national on NPR's Weekend Edition, prompting a flood of support. "Native women from all over the world were contacting us," Nordlum recalled. Many wanted to know what the process entailed, what the patterns signified, where they could get tattooed. Nordlum discovered a need to educate. As an artist, she decided to make a documentary film.

Nordlum, with videographer Tanya Telemaque, launched the documentary earlier this year. Aside from two grants, Nordlum is largely self-funding the project with family and friends.

"This program, I feel, is the most important work I've ever done," she explained. "[It's] bringing back something that is Inuit at heart, healing community and bringing women together in a positive way."

Holly takes a first look at her traditional Inuit tattoo, as artist Maya Sialuk Jacobsen waits in the background, in this 2015 photo. (Photo by Michael Conti / Anchorage Museum)

Identity through ink

Jacobsen returned to Anchorage this October to lead a multi-week tattoo training session for Nordlum and three women who want to continue the tradition. While Telemaque filmed, the five women sat around a workshop table, discussing their shared Inuit heritage.

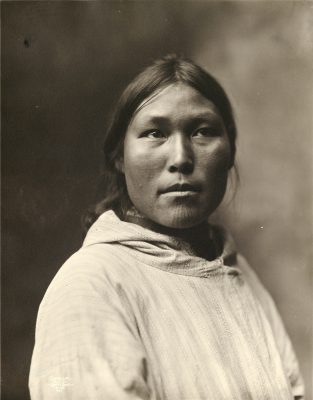

Inuit face tattooing was common as recently as three generations ago, as seen in this 1903 photo. (Alaska State Library, Lomen Brothers Photograph Collection, 1903-1920, ASL-PCA-28)

The tattooed lines symbolize moments in a women's life-reflecting family, marriage, children-and the designs vary by region. But that's the anthropological perspective, gleaned from accounts of missionaries and adventurers, written in Danish, German and Dutch, locked away in library stacks. Jacobsen, in her training, emphasizes the spirituality of the art and the undeniable feeling of connection to the past.

Despite the changing times, the original message-signifying female achievements-remains. "Every Native woman I know who's interested in getting [a tattoo] not only wants to recognize her ancestry, but [what] she's accomplished," Nordlum explained.

"Part of the film is how we adjust. This was common here, this was beauty, this spoke of status in the community and what you've accomplished," she continued. "Now, it's an interesting dynamic; two generations later, people don't know who you are. They think it's a trendy thing."

Nordlum and Jacobsen dream of sharing their knowledge across the Arctic, training Inuit women in Greenland, Canada, Russia and Alaska so face tattooing-often stigmatized in the West-is again normalized in the North.

"It isn't easy for people to accept something outside of their boxes," Nordlum said of the response she's received from uninformed strangers, particularly Alaska's many tourists. "We get dirty looks all the time [and] picture-taking without permission ... It's very exoticized and that's not why I did it. I didn't do this to be a tourist attraction."

Documentary records a shifting story

The finished documentary will address reactions from community, the positive and negative, as well as the history and healing of tattooing.

Likewise, the film will address the clash of modern regulations and indigenous practice. Since starting the project, Nordlum has found herself mired in policy paperwork, arguing the differences between licensed tattoo studios and cultural tattooing. For help, Nordlum turned to her alma mater to talk with UAA political science professor Dalee Dorough, who sits on the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. "Really it's about Native rights and sovereignty and not about a license," Nordlum noted of the ongoing regulatory roadblocks.

The policy problems have become an intractable part of the documentary, providing a contemporary chapter to Nordlum's discussion of hardships and healing in her community. Clearly, both the documentary and the revitalization are works in progress. But thanks to social media connecting interested women across the Arctic-and Sundance connecting Nordlum to potential distributors-there's much to look forward to.

For now, her team is back to educating and filming, recording Jacobsen's October workshop on the practice, the patience and the power of Inuit tattooing.

That was the scene earlier this month, in a back room of the Alaska Native Heritage Center. Five native women-with one behind the camera-poring over packets of designs from across the Arctic, laughing, learning and preparing for what's next.

"I wish my mom could have seen this," Jacobsen said to the small group gathered around the table, smiling warmly as she turned the next page.

Written by J. Besl, UAA Office of University Advancement

"Reviving Inuit identity through ink" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Reviving Inuit identity through ink" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.