Safe in the Sound: tailoring forecasts for the challenging Chugach

by joey |

Atmospheric Scientist Peter Olsson uses climactic physics to pinpoint forecasts on the unique geography of Prince William Sound. (Photo by Phil Hall / University of Alaska Anchorage)

If you're heading out for a hike in the Chugach, you can check your phone's weather app. If you're steering an oil tanker across Prince William Sound, you might want a bit more information.

The Alaska Experimental Forecasting Facility (AEFF) is here to provide those high-resolution weather forecasts specifically tailored to the incredible - and incredibly challenging - area around the Chugach Mountains. AEFF forecasts benefit the ski guides, sport fishermen, ferry captains and prop-plane pilots who make their livings (and risk their lives) on the region's volatile land, sea and sky.

"In a sense, we downscale and extend a National Weather Service [NWS] forecast," explained Peter Q. Olsson - Alaska's state climatologist and the chief scientist at the AEFF. NWS maps the entire world, while AEFF covers just the area surrounding Prince William Sound and Cook Inlet. "We just take a postage stamp of the map of Alaska," Olsson noted.

The Chugach Mountains create a weather conundrum that broader NWS models can't resolve. For example, Mount Marcus Baker-the highest peak in the range, at 13,176 feet - is just 11.12 miles from Prince William Sound. That abrupt transition from base to summit places Marcus Baker among the most topographically prominent mountains in the world, and creates a significant barrier for weather systems to overcome. That topography helps make the Sound so choppy and the Matanuska Valley so windy each winter.

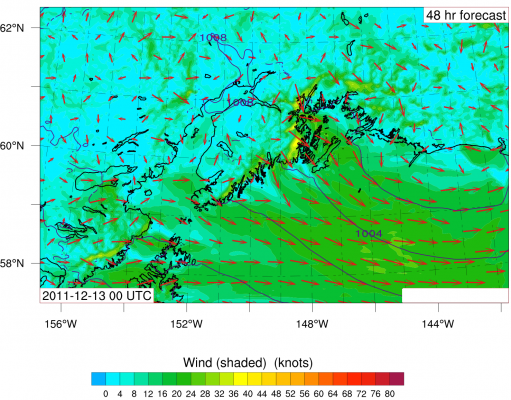

The "postage stamp" the AEFF covers includes the volatile region around Prince William Sound and Cook Inlet (Image courtesy of AEFF).

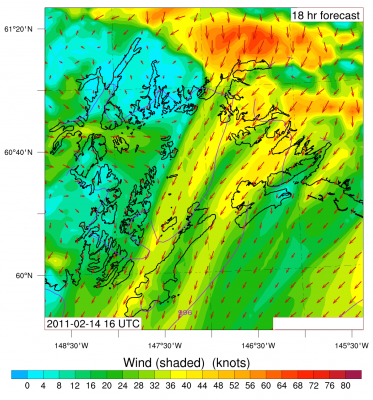

As Olsson explained it, the Chugach Mountains block cold air from the Interior, creating cold-air domes that deepen and intensify until they reach an elevation of escape.

"Once the cold, dense air makes it through the passes, it pours down in a drainage flow just like water would if you had a little notch in the edge of your bathtub," he said.

To keep Alaskans safe and knowledgeable, the AEFF uses local observations and smaller modeling schemes that account for factors like intercoastal temperature differences, multiple cloud layers and the abrupt Chugach peaks. The finer-scaled model can provide a significant improvement over coarser models from NWS. Like many things, this approach involves a tradeoff - the AEFF sacrifices a large region of coverage in exchange for resolving local atmospheric conditions in more detail.

From the facility's headquarters at the University of Alaska Anchorage, computers take NWS info and refine the parameters, adding elements of physics like surface drag, turbulent fluid mechanics and motion on a sphere (like a true scientist, Olsson - who holds a Ph.D. in atmospheric science from Colorado State University - has an office whiteboard scribbled with complex equations). AEFF's process takes several hours, but the result is "high-resolution, short-term guidance" those in the know can use to stay safe.

"We don't issue words at all, we issue plots," Olsson explained. AEFF's publicly available graphics depict the expected precipitation, temperature and wind speed for the region, but it's up to the user to interpret the results. "We just provide the plots to other savvy users who can tailor it to their needs."

To that end, Olsson's role involves a bit of outreach, though not as much as he would like. A primary client for AEFF's information is the Prince William Sound Regional Citizens' Advisory Council - a Valdez-based nonprofit that unites regional stakeholders, from tribes to tourism bureaus. The Council - made of fishermen, not scientists - contracts Olsson to educate local users on how AEFF data can predict avalanche danger, advise oil spill response and everything in between.

This AEFF forecast indicates a northerly drainage flow over Prince William Sound. In this case, oil tankers would experience winds of 50 knots-or 58 miles per hour-while nearing Valdez (Image courtesy of AEFF).

Likewise, at UAA, Olsson teaches an aviation course on elements of weather, training students to detach from forecasts and recognize the science of the atmosphere in action. "I want the person sitting in that pilot seat to be able to look out that window and judge what's going to happen in the next 10 minutes," he said. Though the course material stays simple, Olsson says its principles are based on "stealth geophysics."

AEFF information is available online in streamlined graphics and charts (the raw weather data would likely crash a home computer). If you want the basics delivered by a friendly face, tune into the news. If you want pinpoint reports on Prince William Sound, turn to the AEFF.

"It's a place where you could really get in trouble," Olsson noted of the volatile weather area. As the state's climatologist, he's occasionally summoned to court to certify data in cases where weather played a role, including drownings throughout the region.

Weather is timeless, but the equipment has changed since Olsson founded the AEFF in 1999. "Computers, you can't keep up with them," he laughed, gesturing at the tangled cables of cords snaking around the room.

But he continues to refine and polish the algorithms, cutting down prediction times and enhancing accuracy levels as technology improves.

Why? In Alaska, he says, "there's a lot of pressure to make good decisions in a short amount of time."

See data and daily reports on the Chugach region at aeff.uaa.alaska.edu.

Written by J. Besl, UAA Office of University Advancement

"Safe in the Sound: tailoring forecasts for the challenging Chugach" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Safe in the Sound: tailoring forecasts for the challenging Chugach" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.