'How do we make science a better place?' — The McLaughlin Lab comes to UAA

by Keenan James Britt |

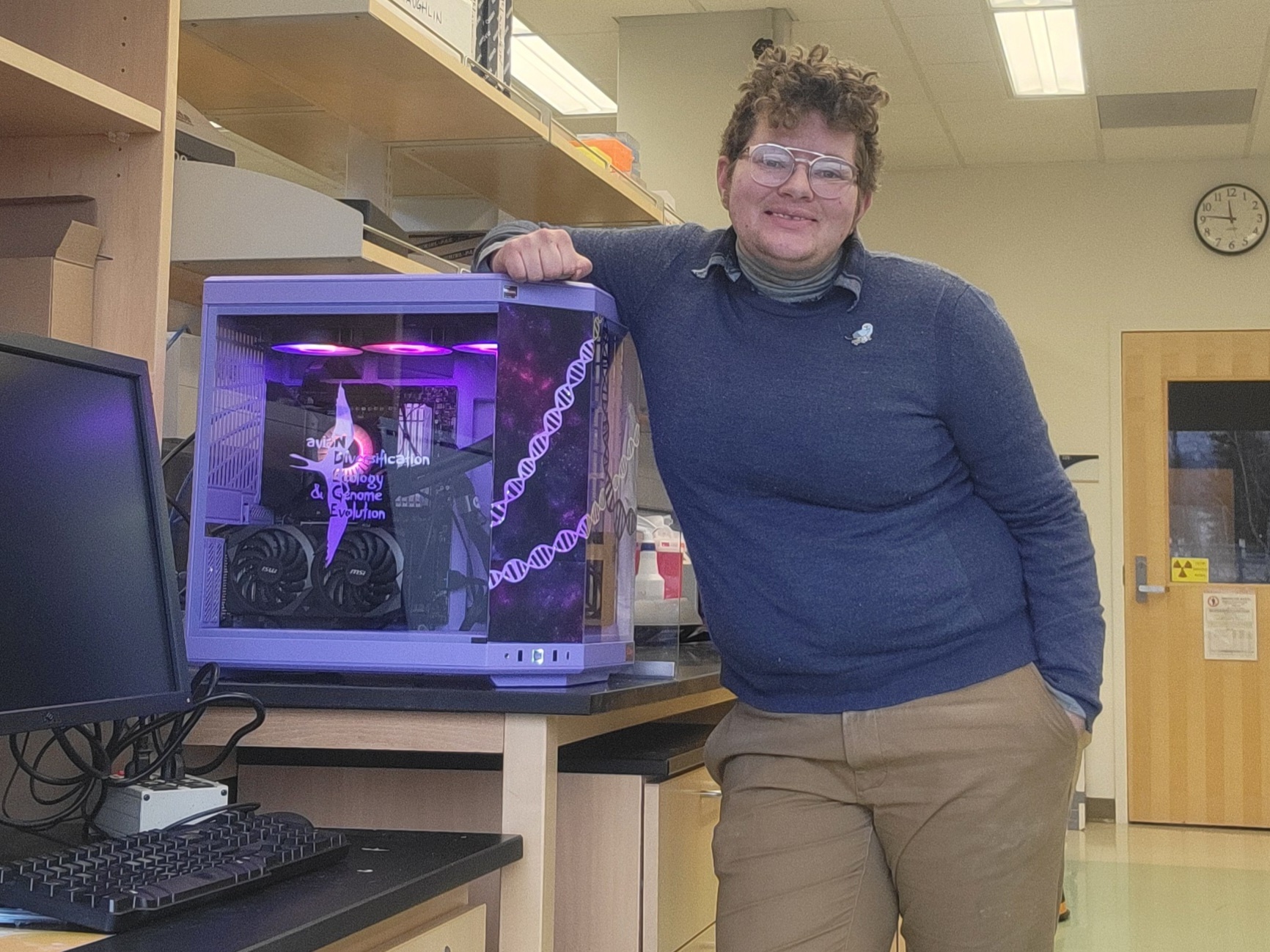

The McLaughlin Lab launched this semester at UAA, with principal investigator Jess McLaughlin, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, placing ethics at the forefront. McLaughlin is recruiting graduate students for the 2025-26 academic year and is actively thinking about how to prioritize students and local communities.

These commitments are part of McLaughlin’s core values. The McLaughlin Lab’s website hosts an ethos and values statement that reads, in part: “We’re not just committed to doing good science — we’re also always trying to do better as people.”

Putting students first

Recalling their experience as a graduate student, McLaughlin stated: “I really enjoyed a lot of aspects of grad school, but there's a lot of aspects of it that are very hard. Some of that is just because science is hard. But a lot of it's because sometimes the people who do science [...] forget how to be people you want to work with, and kind of make it a little bit harder than it needs to be.”

McLaughlin intends for their lab to be a welcoming place for future students. “There's plenty of obstacles already in doing science. We don't need to be going and putting in extra ones,” McLaughlin explained. “I can't make that experience completely go away for students [...] but I can do my best to try to make it so that that's not something they have to face in the spaces I do have control over.”

McLaughlin also describes themself as “an advocate for equity in STEM, especially for LGBTQ+ inclusion.” Early this year, they were a co-author on a publication in the scientific journal Cell, “Rigorous Science Demands Support of Transgender Scientists.”

Originally from Dayton, Ohio, McLaughlin’s experience as a graduate student began at UAF, earning a Master of Science in biological sciences in 2017, followed by a Ph.D. in biology from the University of Oklahoma in 2022. Afterward, McLaughlin held postdoctoral positions at UC Berkeley and the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

While at Berkeley, McLaughlin learned a valuable lesson from their postdoctoral advisor, Ian Wang, Ph.D. “When I first started there,” McLaughlin explained, “he told all of us there’s two requirements for being in this lab. One thing is you have to be a good scientist. But the other thing — and the more important thing — is you have to be a good person.”

Engaging local communities

Much of the McLaughlin Lab’s research focuses on understanding gene-flow and hybridization between different populations of birds. McLaughlin has focused on the two distinct regions of the world — Beringia, where North America and Eurasia meet, and the Isthmus of Panama, where North and South America meet.

“Working in different systems allows me to get views on different parts of the evolutionary process,” explained McLaughlin, who is fascinated by the diversity in Panamanian birds. “[The Isthmus of Panama] is similar in size to the Mat-Su Borough, yet there’s a thousand species of birds there.” McLaughlin is interested in comparing gene flow within bird species in Panama to those between Russia and Alaska, asking: “What can we tell about the history of this landscape from that?”

McLaughlin has conducted fieldwork in both Panama and Alaska, and the McLaughlin Lab website contains a land acknowledgement for both regions. McLaughlin believes it’s important to “be respectful working on this land that’s native land — both here and in Panama.”

McLaughlin also values making the lab’s research valuable to people in these regions. “I've been doing a lot of thinking and planning around my projects here in Alaska.” McLaughlin explained, “they're not just things that are interesting to me, but things that are of value to local communities, and especially our local Alaska Native communities.” In the future, McLaughlin would like to make gene sequencing more accessible to remote communities within Alaska using smaller, field-based, portable gene sequencers. “You can be in a remote village, sampling an organism that the community has questions about, and you can, for relatively low cost, [...] sequence it and start to get answers. And that means you get greater community involvement.”

These commitments are part of a driving question for McLaughlin: “How do we make science a better place?”

"'How do we make science a better place?' — The McLaughlin Lab comes to UAA" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"'How do we make science a better place?' — The McLaughlin Lab comes to UAA" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.