Project 49: Jack Roderick

by Tracy Kalytiak |

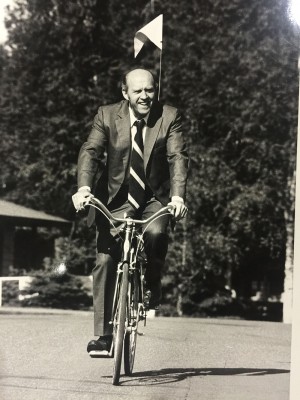

Jack Roderick launched the People Mover public transportation system while serving as mayor of the Greater Anchorage Area Borough. (John R. "Jack" Roderick papers, Archives and Special Collections, University of Alaska Anchorage)

Do you ride a People Mover bus to school or work? Do you like having a community council "voice" in what happens in your neighborhood? Do you enjoy running and bicycling on Anchorage's trails or taking your kids outside to play in its green expanses?

If you answered "yes" to any of those three questions, you have Jack Roderick to thank.

Jack championed each of these then-visionary initiatives while serving as mayor of the Greater Anchorage Area Borough from 1972-1975, the year voters chose to merge the warring city and borough of Anchorage into one entity: the Municipality of Anchorage.

While Jack is best known for leading the borough of Anchorage into an era of pipeline-financed comfort, he had spent almost all of his life growing an incredible résumé of talent, initiative and accomplishment.

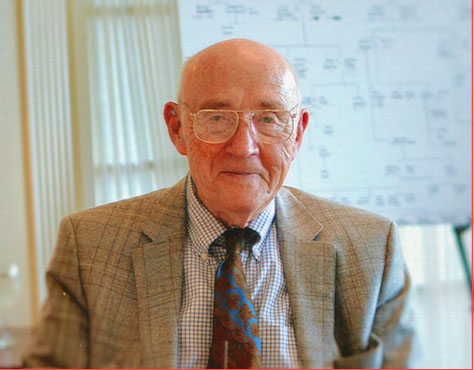

Jack Roderick served as mayor of the Greater Anchorage Area Borough from 1972-1975. (John R. "Jack" Roderick papers, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage)

One of his accomplishments? Writing a fascinating 1997 book, Crude Dreams: A Personal History of Oil & Politics in Alaska, detailing the birth and development of the new state and an industry that made it rich.

The UAA/APU Consortium Library's Archives and Special Collections has 19 boxes filled with files containing legal and government documents, book drafts, photographs, newspaper and magazine articles by or about Jack, and recorded interviews he made or unearthed while researching Crude Dreams-recordings of people that included his law office colleague-turned-U.S. senator, Ted Stevens; Alaska geologist, aviator and legislator Irene Ryan; former Alaska governors Walter Hickel, Steve Cowper and Jay Hammond, former Alaska First Lady Neva Egan, and Willie Hensley, an Alaska Native rights advocated who championed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

'I jumped down to the tarmac and ran'

Jack has grown a rich life in his nearly 90 years, engaging successfully in a series of vocations: student (he earned degrees from Harvard and Yale, in addition to the University of Washington), Navy pilot, star football player, teacher, coach, publisher of an oil scouting report and other publications, businessman, lawyer, state official, Peace Corps director, mayor, professor and author.

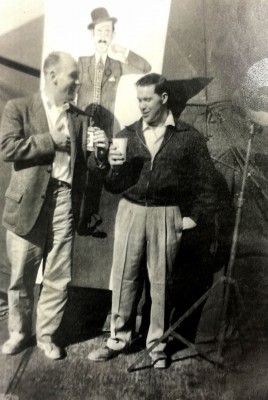

Jack Roderick, left, stands with Locke Jacobs, a self-taught geologist credited with finding Alaska's first commercial deposit of oil, in the Kenai Moose Range. (John R. "Jack" Roderick papers, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage)

He grew up in Seattle, the son of a Presbyterian minister who met Jack's mother while serving in France during World War I. His parents divorced when he was 11, but Jack flourished at school, running track and playing basketball and football.

He began attending the University of Washington, and, as a freshman, played football until joining the U.S. Navy Air Corps. He was a star athlete with a talent for getting open on the gridiron-so skilled he later turned down an offer to play for the Chicago Bears.

In 1949, Jack miraculously walked away from a chartered and overloaded DC-6 that crashed while taking off from Seattle's Boeing Field, killing 14 other students returning to Yale after Christmas break.

"My shoes came off and the seats broke and went forward, but my belt held," he said. "I went out the cargo door, jumped down to the tarmac and ran. I thought everyone was going to get out, until I saw the plane broken in half and burning. We tried but there wasn't much we could do."

Later that year, Jack earned a bachelor's degree in political science at Yale. He coached and taught at a Michigan high school before returning to UW for a year of law school, according to an Anchorage Press article tucked in one of Jack's archive files.

He was living in New York after college when a friend told him about working at a cannery in Alaska. "In 1952, the 26-year-old, in debt to his roommates and to Yale University, decided to head north to work at a cannery in Afognak, an island just north of Kodiak," the article said. "'It was good money,' he says. 'I did it because I needed the dough.'"

Afterward, he lived briefly in San Francisco before moving back to Anchorage and driving a truck between Fairbanks and Anchorage. While visiting Seattle for Christmas, he met a woman from Tennessee who had recently graduated from Radcliffe College. Martha Brady Martin moved to Alaska and became a flight attendant for Cordova Air Service. She and Jack married in 1955 and within three years were raising two daughters: Selah and Libby.

Eight subscribers and a wife

When Jack's employer went bankrupt, a friend from Shell Oil suggested he start a scouting service. In 1954, Jack launched Alaska Scouting Service, which kept track of oil leasing and drilling activity in the Territory of Alaska. He charged $385 per subscription.

In 1954, Jack Roderick launched Alaska Scouting Service, a newsletter about leasing, drilling and other oilfield-related activity in Alaska. (John R. "Jack" Roderick papers, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage).

"At the end of a year, he had eight subscribers and a wife," according to Crude Dreams. "He decided to finish law school so he took the mimeograph machine with him to Seattle and returned to Anchorage during summers."

Jack earned his law degree at the University of Washington and then began investing in oil leases as one of the "little guys" at a time when Alaska hoped to become a state and take control of its own affairs.

Richfield found oil at Swanson River in 1957, creating Alaska's first producing oil field, an event that accelerated Alaska's progress toward statehood two years later. Then, in 1967, Richfield found a massive source of oil at Prudhoe Bay. Construction of the trans-Alaska oil pipeline began in 1973, after passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971.

Against this backdrop, Jack launched businesses and limited partnerships and "practiced as equals in the law firm of Stevens & Roderick" with Ted Stevens. U.S. Sen. Bob Bartlett died in 1968, and Alaska Gov. Wally Hickel appointed Stevens to be Bartlett's successor.

"We each paid half the bills, and we were friends," Jack said. "When Wally appointed Ted senator in late 1968, I'd just returned from India. Ted asked me to take over his practice, which I did."

Jack and Martha had moved their family to India when Jack was tapped to serve as a regional director of the Peace Corps in India, from 1967-1968.

"Martha and I liked the idea of the Peace Corps," Jack said, in a recent interview. "India is a fascinating place, the largest democracy in the world. I signed up for a couple of years but only lasted a year there because I had played a lot of football, was sitting in my office and my left arm went to sleep. My neck had collapsed. They put me in a brace. I had to have a couple of surgeries on my neck."

'A few Assembly members may still curse me'

Jack became mayor of the Greater Anchorage Area Borough in October 1972 after an election that pitted him against 10 other candidates, according to Anchorage Remembers, a 49 Writers Anchorage Centennial memoir project.

Jack Roderick spends time with his wife, Martha, and their daughters, Libby and Selah, in this photo taken in 1972. (John R. "Jack" Roderick papers, Archives and Special Collections, University of Alaska Anchorage).

"I had no experience in government service but knew my background made me a good fit for the job of mayor," Jack said, in that article. "Years as a pipeline industry consultant and lawyer convinced me that Anchorage was poised to experience significant economic development. Tim [McGinnis] helped me ... develop a platform that would later become an action plan for my years as mayor: government that is responsive to all citizens and not just the few; taxes and government services that are restrained and made cost-effective; organized land-use planning and quality public transportation."

Jack said his campaign focused on maintaining Anchorage's quality of life and supporting more bike paths and greenbelts. His proudest accomplishment? The creation of community councils.

"I assume that a few Assembly members may still curse me for having encouraged nonelected citizens to take the time to fashion their own strong-and mostly well-thought-out-opinions before taking their concerns and complaints to the Assembly," Jack said.

Jack served as deputy commissioner of the Alaska Department of Natural Resources in Gov. Jay Hammond's administration. He earned a master's degree at Harvard University and was Littauer Fellow at its John F. Kennedy School of Government in 1980-1981. He taught a course about oil history at Alaska Pacific University and business law at UAA. Later, in 2005, UAA gave Jack an honorary doctorate of laws.

Jack Roderick was one of the former Anchorage mayors who took part in UAA's Seward Lectures, organized by the Department of Political Science.

"It must sometimes feel to elected officials like democracy is about to unravel," Jack said. "I hold the opposite view. The essence of democracy, I believe, is public participation. And now with our community councils, Anchorage has the right balance for a healthy community."

Want to learn more about Jack Roderick's colorful life and Alaska's early days as an oil-producing state? Check out his papers, photos and recordings at the UAA/APU Consortium Library Archives and Special Collections. Click here to listen to Jack's mayoral recollections as a participant in the 2015-16 Centennial Mayors talks for last year's Seward Lecture series, sponsored by the UAA Department of Political Science. All the Centennial Mayors can be found at this link; more will be added in Spring 2016.

Written by Tracy Kalytiak, UAA Office of University Advancement

"Project 49: Jack Roderick" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"Project 49: Jack Roderick" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.