What happened when Juneau took fluoride out of the drinking water?

by Matt Jardin |

Over the last three years, assistant professor of health sciences Jennifer Meyer, Ph.D., M.P.H., C.P.H., R.N., delved deep to find out what happened to Juneau after the community voted to remove fluoride from their drinking water in 2007. (Photo by James Evans / University of Alaska Anchorage)

According to Healthy People 2020 approximately four out of five Americans have access to optimally fluoridated water (OFW). That figure comes from assistant professor of health sciences Jennifer Meyer, Ph.D., M.P.H., C.P.H., R.N. In Alaska, the percent of the population with access to OFW has dropped significantly from 60 percent in 2007 to only 42 percent in 2017.

Among the percentage of communities without fluoridated drinking water is Alaska's capital city, Juneau, which voted to carry out the cessation of community water fluoridation (CWF) in 2007.

Juneau's decision to remove fluoride intrigued Meyer and was the impetus for her recently published paper about the impacts of CWF cessation on children and adolescents eligible for Medicaid.

"The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified community water fluoridation as one of the top 10 most important and effective public health interventions of the last century," said Meyer. "That's why I was interested in looking at the community effects of removing it. Also, as a mom with a newborn, I was concerned about my son growing up without CWF and what that might mean for his future oral health."

In the study, Meyer and her co-author, oral health epidemiologist, dentist and Walden University faculty member Dr. Vasileios Margaritis, decided to examine the Medicaid dental claims records of two groups of children and adolescents aged 18 or younger.

Group 1 consisted of 853 patients who filed Medicaid dental claims in 2003, four years before Juneau's removal of fluoride in 2007. This group represented what the researchers considered optimal CWF exposure.

On the opposite end was group 2, representing patients living under sub-optimal CWF conditions. This group was made up of 1,052 patients with Medicaid dental claims records from 2012, well after Juneau's fluoride cessation.

"In many ways, Juneau was a perfect community to study because of its isolation and low population growth," said Meyer. "It doesn't have a lot of in-and-out migration or nearby fluoridated communities that can be confounding. We hypothesized that children with the least amount of exposure to optimal CWF would suffer more cavities and increased restorative costs. This turned out be supported by the analysis and results."

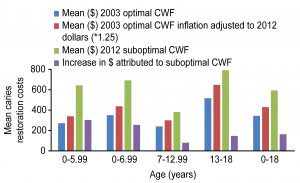

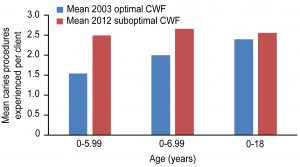

With the data sets in place, Meyer began the painstaking comparison of the records. She found that patients from the sub-optimal CWF group had greater odds of experiencing a cavity - or caries - related procedure. The binary logistic regression analysis results indicated a protective effect of optimal CWF for the 0- to 18-year-old sample and for the age groups less than 7 years old.

Additionally, the age group that underwent the most dental caries procedures and incurred the highest caries treatment costs on average were those born after CWF cessation.

For many children and their parents, the idea of having to visit the dentist one extra time each year isn't a welcome one. Meyer estimated that the average inflation-adjusted cost of each additional cavity procedure was approximately $300 per year for each child in this young cohort.

"We thought that cost was a good proxy for severity," said Meyer. "There's also broader community cost because the children analyzed in the study were on Medicaid and that is a taxpayer-funded program."

Despite Dr. Meyer's study, Juneau officials remain unswayed. In a story published one month after the release of the research, The Juneau Empire relayed that the capital had no plans to reintroduce fluoride into the community's drinking water.

Still, the timing of Meyer's report seems somewhat serendipitous as similar studies scrutinizing efforts to remove fluoride from water have surfaced recently in academe.

Meyer cites one particular report from Windsor, Ontario, that was also released in December 2018 around the same time of her study. Recently, the Windsor City Council voted 8-to-3 to reinstate CWF. The move came five years after their own fluoride cessation program when they started tracking the population's oral health. The study's findings were similar to that of Meyer's - tooth decay increased among Windsor children requiring urgent care by 51 percent.

Windsor's move to reverse public health policy course gives Meyer hope that communities are becoming more willing to examine CWF study data and use it for decision-making purposes.

"We add and supplement beneficial elements in food for many reasons," Meyer said. "It's an effective and equitable public health strategy. For example, we fortify wheat products with folic acid to prevent spina bifida and other neural tube defects. We add calcium and vitamin D to milk to prevent rickets, and adding iodine to salt has been a primary way of preventing iodine deficiency and goiters. Similarly, fluoride is an important mineral for the development and protection of teeth. Adjusting the availability of fluoride in the community water to an optimal level (0.7ppm) supports a population oral health benefit and mitigates risk."

Dr. Meyer and Dr. Margaritis recommend everyone practice good oral hygiene at home (brushing and flossing twice a day, using a fluoridated toothpaste), visit a dentist regularly for cleaning and preventative care (mostly sealants and application of topic fluoride products twice per year), eat a healthy diet low in sugar and drink fluoridated water.

According to Meyer, "CWF is one of several methods for reducing the risk of cavities and the best part is it requires no individual behavior change or action to receive the benefit."

Written by Matt Jardin, UAA Office of University Advancement

"What happened when Juneau took fluoride out of the drinking water?" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

"What happened when Juneau took fluoride out of the drinking water?" is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.