University of Saskatchewan Collaboration

By Jessica Ross, Nughejagh Founder

I had the opportunity to meet with Professor Stacey Lovo of the University of Saskatchewan.

Professor Lovo is an Assistant Professor who works in the School of Rehabilitation

Science and also serves as an Associate Member of the Department of Surgery within

the College of Medicine. I took the two and a half hour drive to Saskatoon today to

tour the University of Saskatchewan and to learn more about the programs the organization

offers, especially pertaining to Indigenous Health and Culturally Responsive curriculum.

I had the opportunity to meet with Professor Stacey Lovo of the University of Saskatchewan.

Professor Lovo is an Assistant Professor who works in the School of Rehabilitation

Science and also serves as an Associate Member of the Department of Surgery within

the College of Medicine. I took the two and a half hour drive to Saskatoon today to

tour the University of Saskatchewan and to learn more about the programs the organization

offers, especially pertaining to Indigenous Health and Culturally Responsive curriculum.

Towards the end of my journey, I noticed the landscape quickly transitioned from flat green grass farmland to densely treed areas. Barn and silos were replaced by grand old brick buildings, designed in a manner that makes me think I am entering into a story book.

Large oak and maple trees line the streets, creating a canopy of much appreciated shade. Although it is summer, the campus still indicates it is still alive as students, staff and faculty walk to and fro. Construction workers are busy working on road infrastructure.

I certainly feel like a duck out of water. During my drive I contemplated on what I should look for during my trip here. But when Professor Stacey Lovo called me and said she was eager to meet and show me around and discuss her work I felt a sense of relief as I finally had a sense of direction.

Stacey was warm and welcoming. It was the first time we had a chance to meet face to face. We have had the pleasure of meeting via zoom a few times prior, but seeing her face, giving her a hug and just being in her presence really validated my draw to this collaboration. Stacey is a true ally for Indigenous people. Her warmth and genuine welcome were indicative of this. Surely zoom can offer some connection, but I would have never been able to have this sense if I had not had the chance to meet Professor face to face.

After I picked up some California rolls with extra ginger, Stacey and I sat down and talked about our roles at the different Universities. Stacey has worked at UASAK for about 15 years, 12 of those in a supportive role, and the last three as a teaching faculty member. Stacey was not hesitant to share with me the barriers to care that Indigenous people face here in Canada and the amount of racism that remains prevalent throughout the country. She was passionate as she spoke about how Saskatchewan’s population is approximately 28% Indigenous, and about famous cases of Indigenous patients that were treated so inhumanely that it resulted in legislation passing and policy changing to encourage change.

Stacey graciously told me that there are two government agencies responsible for Indigenous Healthcare. She told me that people and needs can fall through the cracks as the two agencies will often fight with one another about who will pay for the cost of care, often leaving the Indigenous patient with needs being unmet. She also shared with me the tragic story of a young Indigenous patient who was born with severe disabilities and was never permitted to go home with his family. The patient ended up spending his entire life in the hospital, eventually passing away without ever setting foot on his homeland, experiencing traditional ceremonies, and separated from his family. Stacey’s allyship for Indigenous people was further proven by her storytelling, as she explained these situations with so much expression of heartache and concern.

After we ate, Stacey walked me over to the bookstore that sold all kinds of USASK gear (or swag as everyone lovingly calls it). She excitedly showed me a recent Indigenous Symbol campaign that USASK has endorsed, and which must be a success as most merchandise with these symbols were sold out. I managed to snag a coffee mug. She did show me that the school was also celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Indigenous Teachers program, which I was fascinated with as education is a huge passion of mine (especially Indigenous Education). A section of books solely written by Canadian Indigenous writers caught my attention, leaving me no choice but to add three books to my personal and professional library. Stacey explained that her children are half Metis, and briefly explained the fascinating fact that the Metis are Indigenous to Canada and no where else. Her smile and passion again showed most prominently as she spoke.

After the book store, we ventured through campus sidewalks and came upon a distinct

building on the campus. Among the cathedral architecture of the campus with stiff

straight walls and steep, sharp roofs stood this gem of a building whose walls curved

as if shaped by water. The brick formed an intricate pattern emulating a woven basket

(or at least that is what it reminded me of).

After the book store, we ventured through campus sidewalks and came upon a distinct

building on the campus. Among the cathedral architecture of the campus with stiff

straight walls and steep, sharp roofs stood this gem of a building whose walls curved

as if shaped by water. The brick formed an intricate pattern emulating a woven basket

(or at least that is what it reminded me of).

I was thrilled as Stacey and I turned to indicate that the building was one of our destinations during today’s visit. As we walked Stacey painted a story of the construction of the building, telling me that they had to cut down many trees to create the space, and as appreciation for the trees, the architect decided to use the trees for the interior design. One of the largest trees that was cut down for the structure was actually transplanted into the interior of the building, and it is the first thing you see as you enter the building.

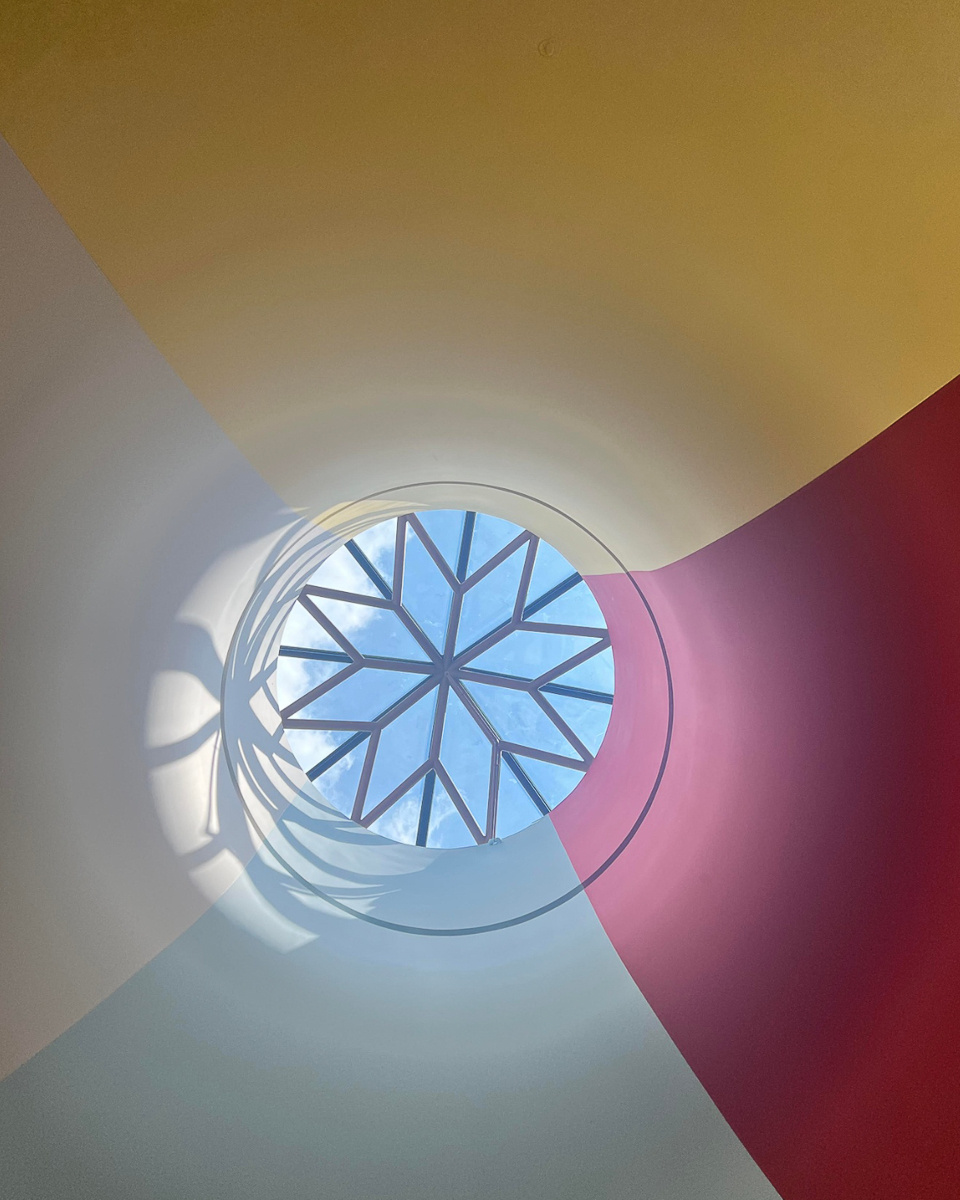

The building was the Gordon Oakes Red Bear Student Centre. A safe haven for Indigenous students who attend the university to practice ceremonies, find support and community, and study. Upon entering I was greeted by a large tree that sacrificed itself for the construction of such a sacred space. Stacey introduced me to Curtis Sanderson, the Clerical Coordinator of the Centre who offered to give us a quick tour of the facility. Curtis guided Stacey and me into the ceremonial space that served as the main space of the building. The ceremonial space is a circular shaped room surrounded by natural light through large vertical windows and a skylight. The brick-laid floor follows the shape of a circle and outlines the sacred circle where ceremonies would take place. Curtis explained to me that during construction, the knowledge keepers overseeing the project insisted that the ceremonial space be genuine, meaning that it would have to be grounded (the floor would have to be in contact with the earth). This proved at first to be a challenge for the designers as the plans for the building called for a basement (under the ceremonial space). Ingenuity kicked in and it was decided that earth from the building site would be dug up and placed in a base that would be attached below the ceremonial space (ensuring that the ceremonial space would be in fact grounded and genuine).

The floor did indeed draw attention, but the light from the skylight also calls for your attention. The ceiling of the building displays an artful rendition of the medicine wheel. The family of Gordon Oakes Red Bear was consulted on the interior design and they called for a medicine wheel to be displayed but insisted that blue replace the black in the wheel (as this is often done in Dene cultures). The center of the wheel meets the skylight which houses a blanket star (as Curtis referred to it) and explained that the skylight opens to “allow smudging ceremony smokes to rise and go into the sky.”

Curtis and Stacey were thoughtful to give me a beat to take in the space before further explaining the other purposes of the centre. Curtis explained that the ceremonial space is used for traditional gatherings, but also serves as a space for students to study. The second floor of the building overlooks the ceremonial space and houses a computer lab and conference rooms. Curtis explains that the centre “serves indigenous students by providing them a safe place to learn, find community, and celebrate their heritage.”

After a hesitant goodbye (as I felt like I could stay in that sacred space forever), Stacey and I left Curtis and the Gordan Oaks centre to head over to the health sciences building. Stacey explained that there is a historical “old” building that connects to the “new” building. The old building fits right in with the cathedral like architectural buildings that scatter around the campus, while the newer building that conjoins it emulates the straight lights and rectangular shapes that indicate a more modern look.

We enter the new building and immediately are greeted by the symbols that Stacey had told me about earlier in the bookstore. The new health sciences building utilized the symbols in their interior design in etched glass along the stairwell’s handrail and railings along the 2nd and 3rdfloor balconies that face the main lobby of the building.

I entered the lobby of the clinic to find a large open space with several doors to my right that entered treatment areas. The lobby houses several pieces of waiting room furniture, and I immediately thought of how much larger this school was compared to the clinic I used to supervise in the dental hygiene program at UAA.

The reception desk was open and three ladies were present. One looked up from her computer and asked politely if I had an appointment. I explained who I was and my interest in the clinic. The three ladies were happy to discuss the running of the clinic. They explained that the clinic is open year round, but offers limited care options in the summer months as there are not as many students practicing at that time. One lady chuckled as she explained that right now they only have about four students seeing patients, whereas during the academic year they have about 72 students working at a time. I was blown away by hearing this. I thought about the stress I would endure overseeing the care of 26 patients a day, and couldn’t fathom how insane it would be to oversee the treatment of 72 patients! The ladies explained how the facility is facing a major reconstruction, as the University wishes to expand significantly (one lady mentioned a 40% increase in cohort numbers).

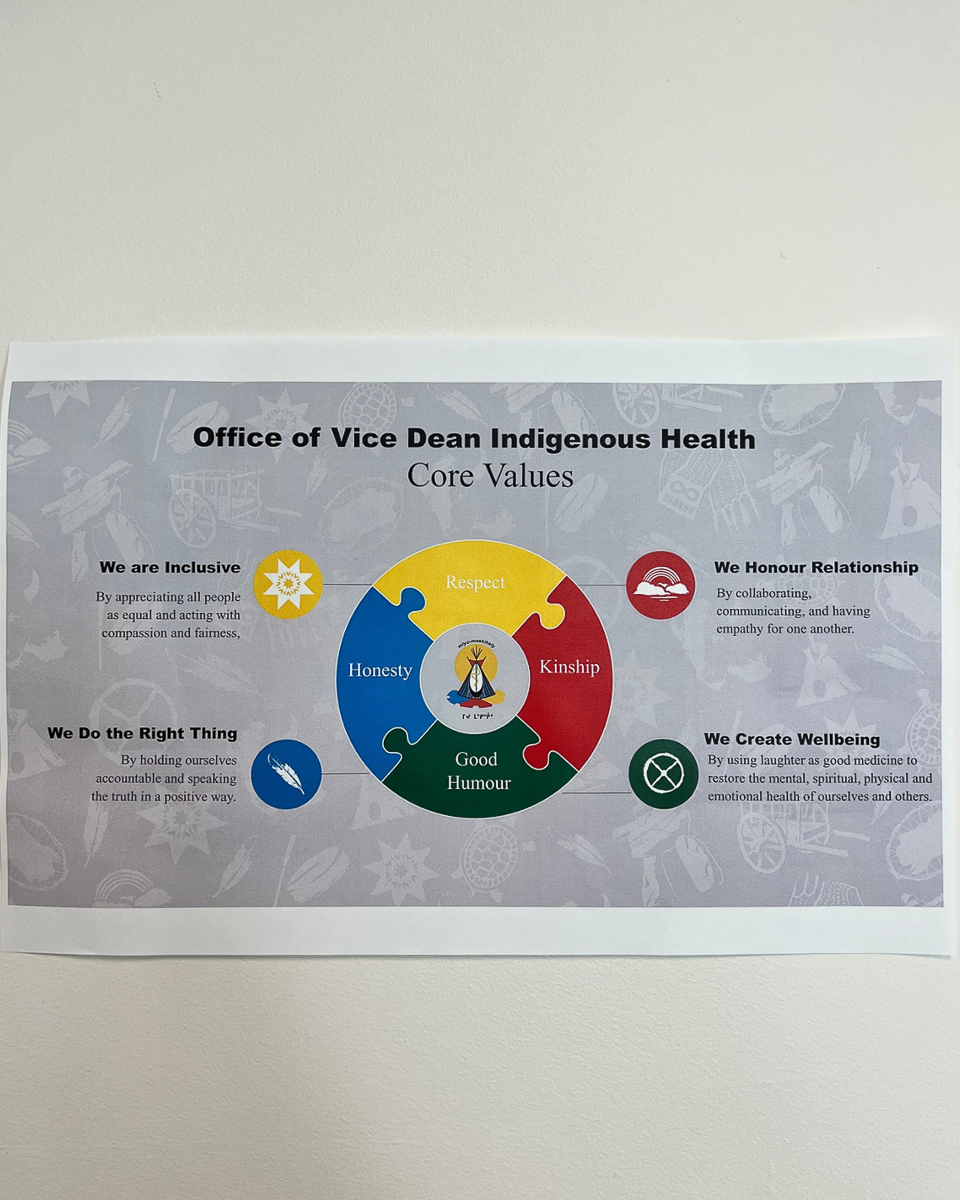

Stacey explained that her department is also being pressured to increase cohort numbers, but quickly changed the subject as she remembered there were other programs and people she wanted to introduce me to. We took the elevator to the fourth floor, where the brand new Indigenous Health department will be housed. Stacey explained that this department is brand new as legistlature has recently passed (like 2 days ago) stating that federal schools would house departments such as these to encourage the enrollment and success of Indigenous students entering into the healthcare field.

She introduced me to Marianne Bell, the manager of the Office of the Dean of Indigenous Health. Marianne greeted us and let us enter into the dean’s office space. She sighed as she explained that they are still in the process of establishing themselves “getting ready for the construction of our ceremony space” which will serve as a study area and space for celebration and prayer for Indigenous students and their families. She explained that she hoped the space would provide a haven within the College of Medicine for Indigenous students to feel accepted and celebrated. She emphasized the importance of the space being open to family members. As she spoke of this I recalled my own time in dental hygiene school where spaces were strictly forbidden to outsiders, and how my views as an Indigenous student were not recognized as scientific enough to be acknowledged.

I realize this observation is not for me to tell my story, but I cannot help but take part in this process as the observations I make and the stories I hear resonate with my own story. My own history. Today’s journey resonated with my own journey through my education, as many of those years I felt compelled to hide my identity from my teachers and fellow classmates.

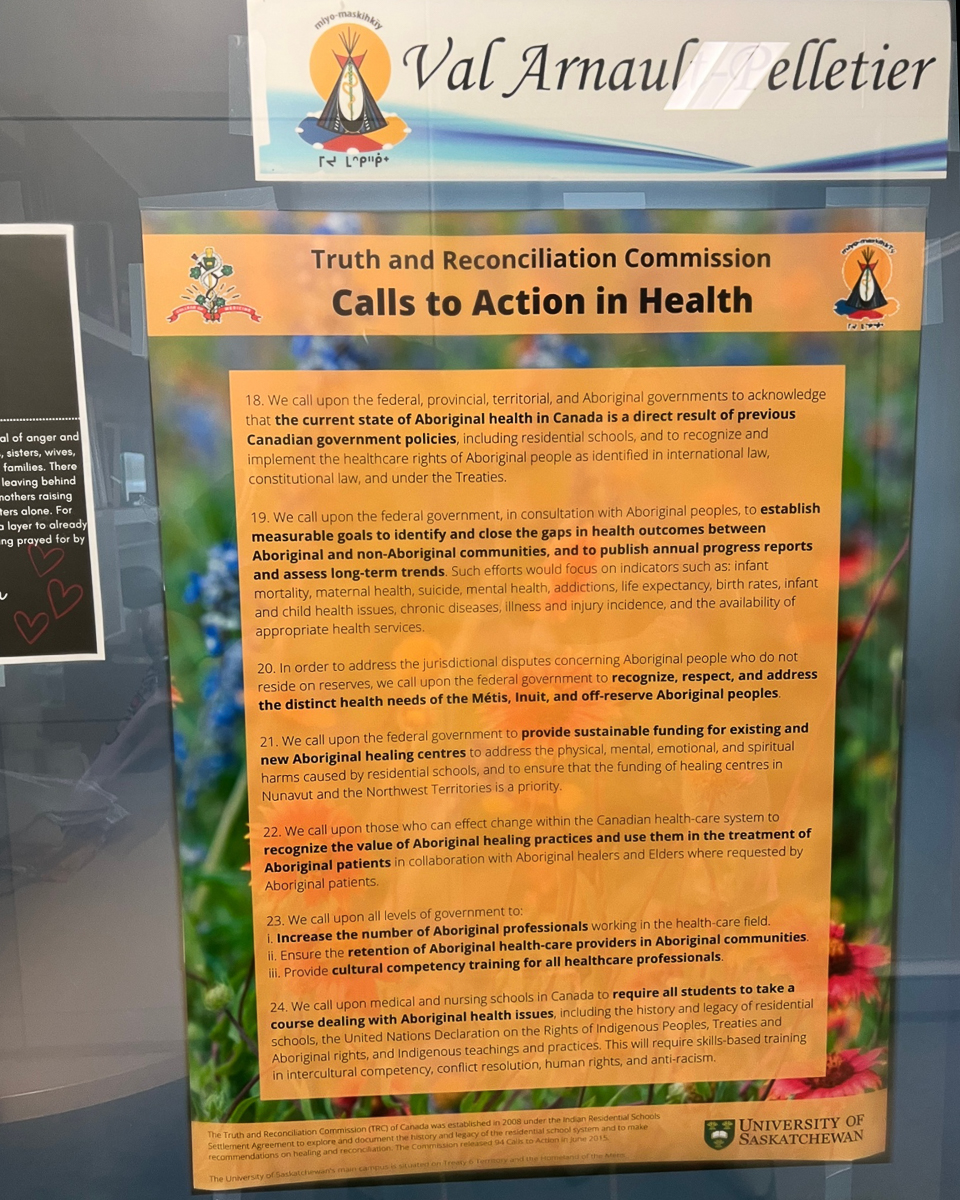

The visit with Stacey ended with a quick walk through the school of Nursing, where Stacey hoped to introduce me to Professor Val Peletier an Indigenous faculty member. But alas this summer visit resulted in the missing out of meeting many Indigenous professors. I made a mental note of my hopes for another visit and plans on who I would want to meet and where I would want to go. I did, however, manage to take a picture of a poster of “Truth and Reconciliation Commisions A Call to Action” that Professor Peletier had on her office door. The poster reminds passers by of actions # 18 through 24 that recognize the hardships that Indigenous people face as a result of poor policy and the requirements of healthcare professionals to engage in Indigenous health in order to better understand and approach Indigenous patients.

Before Stacey and I parted, she encouraged me to visit the school of education, as they have a department dedicated to Indigenous education. She shared with me a map with directions on how to walk there and back to my car. We ended the encounter with another genuine hug and the excitement for future zoom meetings and collaboration on Culturally Responsive curriculum. I walked over to the school of education, admiring and entertained by the little ground squirrels that infested the campus. Stacey had pointed them out to me earlier, and as I crotched down and let out a loud “awwwww” Stacey explained that here in Saskatchewan they are viewed as pests because they destroy farms. I chuckled as I still had the desire to have a “snow-white” moment with the little critters, wanting them to crawl into my hand so I could sing to them.

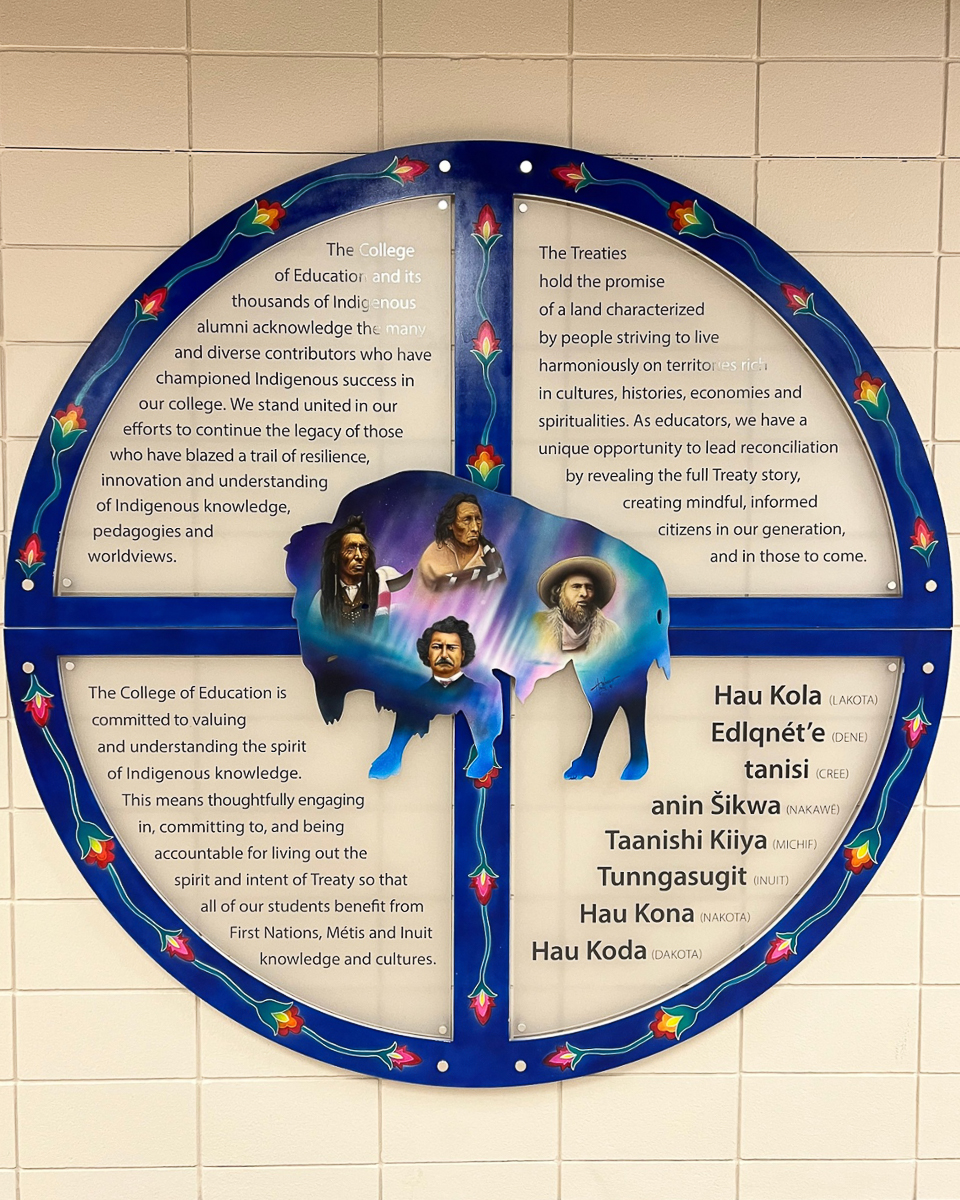

The school of education was quiet, reminding me that I planned this visit at a time when the campus would indeed be sleeping. But I was pleased that the building was open, giving me access to the Indigenous art and information on the Indigenous education program that the school obviously is proud to house.

After my self guided tour I decided to make my journey back across the campus to my rental car. I took a quick drive around downtown Saskatoon and then decided to make my way back to Regina. The day provided me with good intel on the efforts of the University to encourage Indigenous enrollment, especially in the healthcare programs, as well as the recognition of culture, history, and hardships.

The campus reminds all of its residents that colonial history was indeed dominant in the past (with the ornately European like structures built during the establishment of the University), but also reminds residents that Indigenous people are still here, face many hardships as a result of colonization, but are resilient and should be not only recognized, but celebrated in an effort to move forward as a community. The culturally responsive curriculum that USASK utilizes is one such effort of informing and encouraging students to recognize history and embrace/celebrate Indigenous people.